At five in the afternoon, David Ramírez sat in the middle of Panama’s Darién Gap, too exhausted to continue. It was two weeks into his journey from his home in Venezuela to the United States. He had been hiking up a mountain for over three hours that humid, cloudy afternoon to reach the next destination before sunset. The elevation was unbearable and he could not breathe. The physical stress on his body was too much, even for someone like Ramírez, who had been powerlifting for two years.

Ramírez planned the journey with five of his friends and a guide for a year and a half. He had watched YouTube videos of the trip by searching the words “selva” (jungle) and “darien,” but no video had prepared him for the exhaustion and hopelessness he felt sitting inside the jungle at that moment.

“I told my friends to continue, that I wanted to go back. But I knew that whoever enters the jungle will have difficulty leaving it,” Ramírez said.

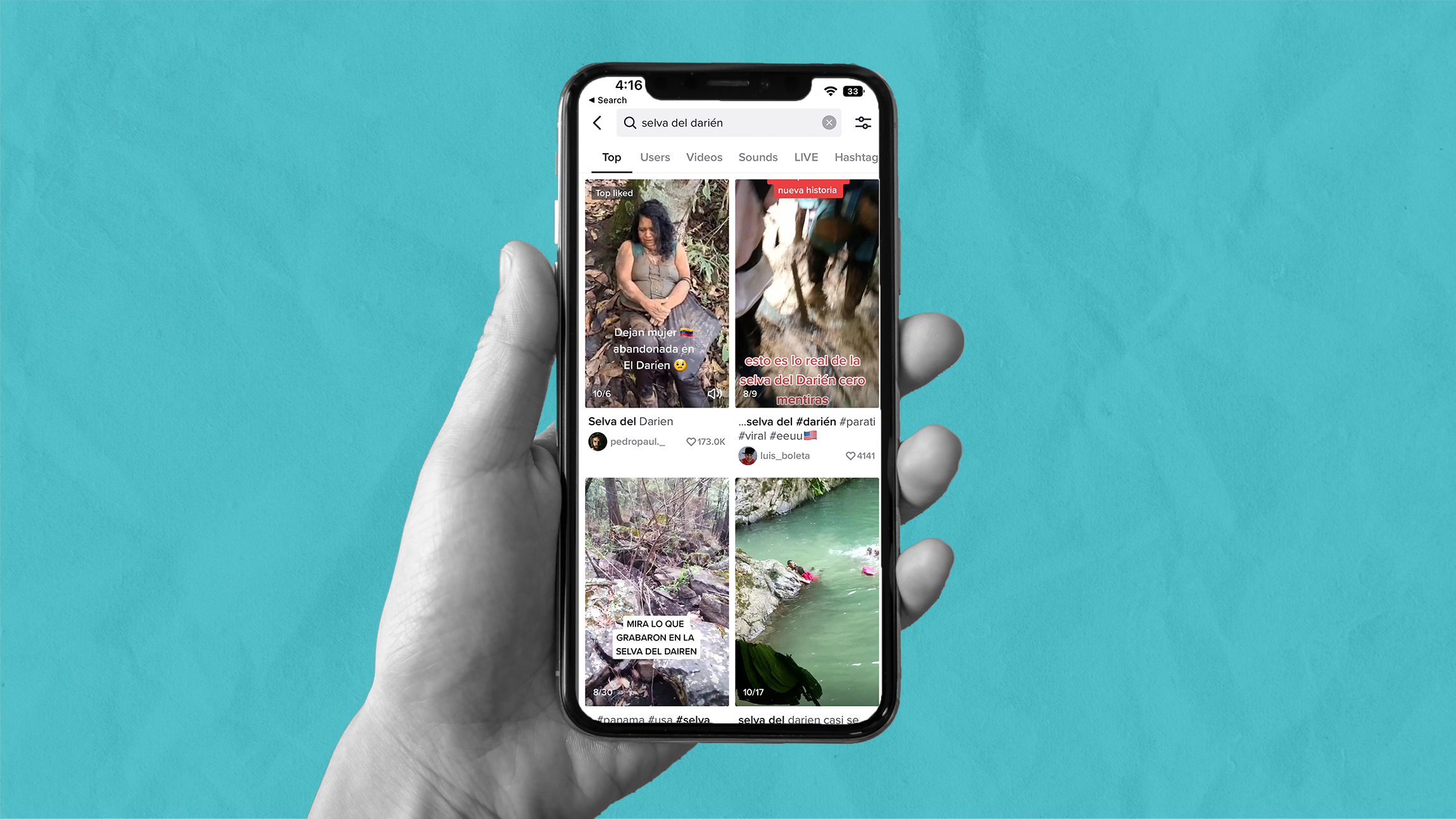

Ramírez vlogged and posted all of his journey on TikTok – where he amassed more than 3 million views across 115 videos, and nearly 30,000 followers, because he wanted to show migrants the obstacles he was facing as he made his way to the U.S. border. TikTok, with more than 1.3 billion users worldwide, has become the platform where migrants – particularly from Venezuela, Cuba, México, and other Latin American and Caribbean countries – share videos of their journeys to warn people of the obstacles they encountered, provide information about the routes they took, and depict the challenges faced by asylum seekers once they cross the border into the United States.

He is one of more than 21,000 asylum seekers that entered New York City’s shelter system since spring of this year. Ramirez resided at a men’s shelter in East Williamsburg for six weeks before fleeing the system when he heard that someone died near the shelter. He went to Indianapolis to live with his friend.

Also Read: New Yorkers Help Migrants Fleeing From Chaotic NYC Shelter System

“The [YouTube] videos only showed the aftermath of the trip, of arriving at the destination. It showed people making it to the peak of the mountain but never showing the road up there… or how I needed to prepare mentally,” Ramírez said.

During the week-long trek in the middle of the Darién, he walked five to six hours daily with minimal food, saw dead migrants buried within bushes, and was constantly anxious because he suffers from ophidiophobia, a fear of snakes, Ramírez said. “I was always scared and panicking after seeing so many snakes. The people coming with me had to kill them,” he said. He also saw a lot of misinformation on TikTok during his journey. He watched videos of people saying that asylum seekers would be placed into shelters as soon as they arrived in the U.S., something he soon found out was not true.

“When immigration authorities let me go [at the beginning of September], I was left on the street. I had no way of coming to New York,” he said. He told Documented that he had to work carrying containers of ice cream for a bodega for one week in El Paso in order to afford his $160 plane ticket to New York City. When he got here, he slept on NYC streets and parks for one week before he got admitted to a shelter. “I see that there is a void of information about what is actually happening during the journey and at the shelters,” Ramírez said.

Because TikTok monitors graphic content, he did not post the videos that included dead people – though he shared them with Documented. Everything he experienced during the month and a half that it took him to arrive at the U.S. border propelled him to create TikTok videos explaining how dangerous the journey is, what it is like to find shelter in NYC, as well the lengths he took to attend his first appointment at 26 Federal Plaza.

“I wanted to show what no one was talking about”

Lionel Baquero cries when he comes across TikTok videos showing parts of the Darién Gap or the Sonoran Desert, he said. Those videos remind him of his two-month journey last year, when he traversed a dozen countries, making more than 30 stops, to make it to the U.S.

Also Read: Leidy Paola Martinez Villalobos Took Her Life At a Queens Shelter. This Is Her Story.

Baquero fled his country of Cuba in September 2021 when he was 30-years-old, and flew to Uruguay. He traveled most of the journey by road. It was during his time migrating that he noticed, like Ramírez, that the majority of the content made by migrants on their travels to the U.S. was celebratory, capturing only the final act of the journey – a huge contrast from the struggles he was facing. “I wanted to show how this journey can be dangerous, which is often overlooked,” he told Documented.

The journey through Darien has also been reported before by other media outlets like New York Times and PBS. However, Lionel wanted to make his own content. “Here is an explainer on why I say Darién is dangerous and why I advise you not to enter it,” Baquero said in one of his many videos on TikTok. He shows the video of a large canoe peacefully sailing in the waters between Necocli, in Colombia, and Acandi in Panama. In the same video, he includes an animation of the 56-kilometer distance that those canoes must sail – and then interposes a screen grab of Google showing sunk canoes where multiple migrants had died on different occasions. “It became clear to me that I could have died,” Baquero says.

He stressed that migration trails are not just physically dangerous, but those who take them are susceptible to threats, extortion, and scams, too. “I wanted to show what no one was talking about,” Baquero added. “Many take advantage [of migrants] because they know you’re carrying money.” Many migrants have also expressed similar experiences to Documented through our WhatsApp channel.

Unlike Ramírez, he posted his first video after arriving in the U.S. He chose TikTok because he had used it professionally before and knew he could reach a larger audience. “At the beginning, I only wanted to tell the stories of migrants like me and help them feel heard,” he said.

Shortly after he posted the video, the views and followers skyrocketed, reaching 361,000 as of mid November followed by companies that wanted to pay him with ad revenue.

A video showing the countries he had to pass through to make it to the states gained 192,600 views, and people accused him of “showing the police routes that migrants were taking,” he said. Baquero disagrees because he says the journey to the states has been public information for years.

Van C. Tran, Professor of Sociology and Deputy Director of the Center for Urban Research at The Graduate Center, CUNY, highlighted the value of the migrant’s testimonies through TikTok. “They are narrating their own lives, and there’s no more reliable narrator than themselves,” he said. Some Latin American and Caribbean communities distrust the mainstream media, contributing to their reliance on peer-to-peer information and social media platforms, which makes them vulnerable to misinformation.

However, Tran also notes that such videos lack encompassing the whole experience of coming to the U.S. because they are created based on individual experiences and only capture their point of view. “By definition, it extracts a portion of reality and allows that portion to represent the entire reality. So, in some sense it takes away complexity and nuances, and reduces to what we call sound bites in journalism,” he added.

DHS limits the entry of Venezuelans to 24,000

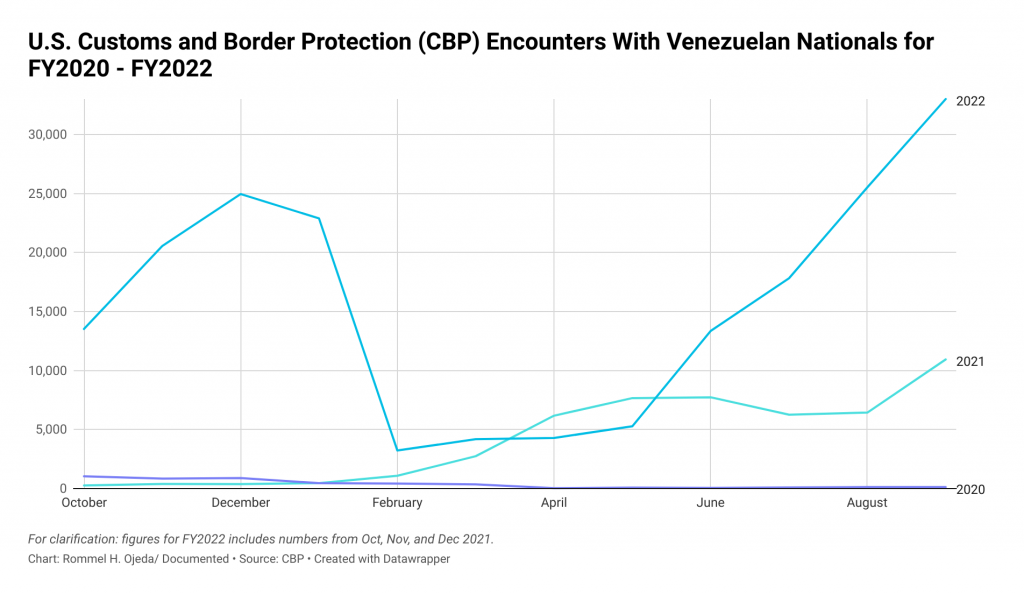

Encounters between U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) agents and immigrants have been on the rise for the past three years, after the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions eased worldwide. This increase is primarily fueled by poverty, natural disasters, and oppressive governments.

Also Read: Border Patrol is Confiscating Venezuelans’ Passports, Causing them Problems for Years to Come

In fiscal year 2022, CBP recorded 188,553 encounters with Venezuelan nationals, more people than Guatemala and Honduras for the first time this year, only second to Mexico. The majority of the asylum seekers arriving in New York City are reportedly from Venezuela, though City officials do not keep track of their country of origin.

As a response to the increase in immigration at the border, on October 7, New York City Mayor Eric Adams declared a State of Emergency to seek federal and state assistance to help deal with the increase of migrants being bussed to the City, and on October 12th, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) implemented new regulations to limit the number of Venezuelans entering the country to 24,000.

Alex, a 23-year-old migrant from Venezuela, who requested to remain anonymous as he is trying to make his way to the states, has also been creating TikTok videos which he shares with his 54,800 followers. He entered the Darién Gap on September 24 and has been in Mexico since October 7. His goal was to submit himself to immigration authorities and seek asylum in the U.S. at the end of October.

“Many people say the jungle is the hardest part, but for me, with all due respect, it has been what happens [after you traverse the jungle],” he said, adding that he had seen posts on social media misrepresenting how hard the journey is. He uploaded his first video of his journey after arriving in Costa Rica in early October. In the video a migrant warns viewers not to come, which made TikTok viewers comment: “you are telling us not to go, but you are already on your way?” he said.

Also Read: Where New Immigrants Can Find Shelter, Legal Help, Food and More

His goal, like Ramírez and Baquero, is to inform people. “I create videos so that people know the realities of going to the United States, and so that they stop falling for fake news and videos that are staged. I’ll continue to show my journey,” Alex said.

On October 12th, he read on social media that the Department of Homeland Security announced new regulations that would send Venezuleans who entered the U.S. without authorization back to Mexico. The following day one of his friends tried to cross the border and was detained by immigration authorities. He was sent back to Mexico.

“Ninety percent of the people have sold their houses and cars. Many have acquired debt to make this trip from Venezuela in hopes of pursuing this great American Dream. After so many saddening moments we have spent on this journey, they close the doors when we are so close,” Alex said.

Since the DHS announcement, CBP daily encounters with Venezuelans dropped from 1,000 to 300. TikTok videos of migrants coming to the U.S. also dropped. The ones that continue to be uploaded are less focused on the journey itself and more on the aftermath of the announcement. Creators like José Silvera started to post videos of the sponsorship guidelines of the DHS ruling, corruption and harassment cases, or about people that have been lost. “I will share videos for my people, for those who are stranded on the way,” Silvera said in a TikTok posted on October 14th, two days after the decree went into effect.

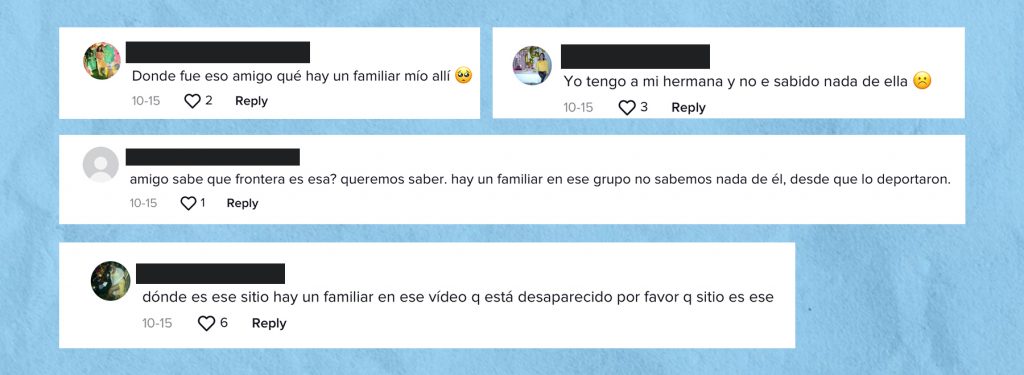

Whereas the people who commented on the videos of Ramírez and Baquero were inquiring about the routes to take, the comments on the most recent videos have shifted to inquiries about what the new regulation meant for Venezuelans on their way to the states. Some have also used TikTok videos to search for their missing relatives. “Please, tell me where this was recorded,” someone commented on a video that showed 20 Venezuelan men being deported.

Content creators have been answering specific questions from viewers posted on their accounts as comments, including the price of moving from certain areas, what has been happening at the shelters, and other topics.

Since the middle of October, Ramírez has been staying in Indianapolis with his friend Miguel, who had also made the journey to the U.S. with him. He says Miguel helped him get a job installing windows in the same company that he works at. The biggest contrast, he says, has been the fact that he is no longer staying at a shelter, as his employer is providing a one bedroom apartment that he shares with Miguel.

On TikTok, he posts videos about the nuances of living in Indianapolis, a far cry from his birthplace of Anzoátegui. During their workday last week, he posted a video of their first snow day. A house in the middle of construction is seen in the backdrop. His friend is on the floor laying and waving his arms, creating a snow angel. It’s a jovial moment, before, with laughter, David says: “Get up, the boss is coming.”

As planned, Alex crossed the border to seek asylum in the United States, but, like his friend, he says he was detained at the U.S. and Mexico border by CBP. He was sent back to Guatemala by Mexican authorities.

Also read: How To Access Emergency Shelter in NYC