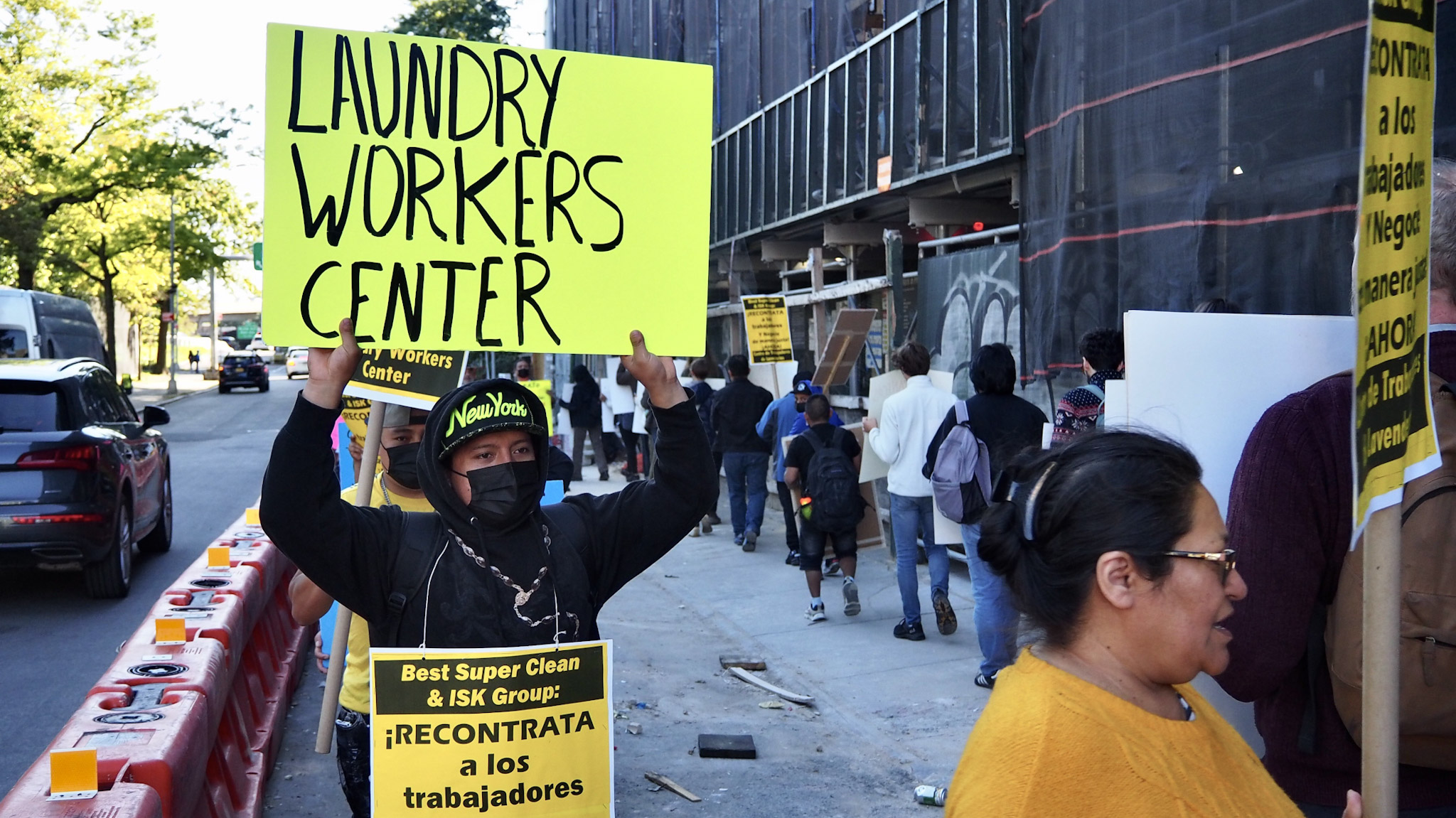

About 40 immigrant indigenous workers at the non-union, Brooklyn-based demolition company Best Super Cleaning, have begun their monthly picket lines outside the company’s worksites again, this time demanding an end to the retaliation and intimidation from their employer.

Last month the workers filed two charges with the National Labor Relations Board, one on March 13 and the other on March 27, charging the company with surveilling its workers’ organizing activity and threatening workers who chose to organize.

Guatemalan worker Adelso Escalante, 21, said the company divided the workers who have been organizing into separate work crews. After speaking to the new hires, he learned the company was giving raises to the new workers who had not joined the campaign, most likely as an attempt to dissuade them from organizing.

“We understood since the beginning, that even if the company divided us as a group, we will stand united,” he said in Spanish.

The workers, who are organizing with the immigrant-worker-led grassroots organization Laundry Workers Center, launched their Cabricánecos Campaign last May. Their campaign called for ending wage theft at Best Super Cleaning, raising their wages from $15 an hour to $17 an hour, and making their workplace safer. The campaign was named after Cabricán, the Guatemalan town many of the workers immigrated from.

Also Read: “At Any Moment Anybody Can Die”: Immigrant Construction Workers Fight for Safety

Fellow Guatemalan worker Wilson Diaz, 26, worked for the company for four years, and like Escalante, attended the most recent picket line on March 17. When workers would complain about their conditions, Diaz said management would belittle workers and threaten to fire them.

“Several of my co-workers suffered humiliation and reprisals from our bosses and that prompted us to organize ourselves,” he said in Spanish.

In addition to increased wages, one of their key demands was the establishment of a workplace safety committee. Escalante, who has also worked for Best Super Cleaning for four years, said the job was extremely dangerous. Workers often went entire shifts without meal breaks.

“We often are forced to work on scaffolding with no harness and work in dark rooms with low visibility,” he said. “They refused to give us breaks and fired workers who spoke up in retaliation.”

Diaz said that if the workers refused to engage in a dangerous task, the company would lash out. “I worked in very dangerous areas where I knew we were going to take risks and if we refused to do it they sent us home or left us without work for a day, that’s how they treated us before.”

After months of worker protests, and with the support of Jewish community leaders, the company relented on Jan. 20. They sent a letter to the workers stating that they would agree to the establishment of a health and safety committee. Workers would be able to meet with management every Tuesday to discuss any safety issues they had with management. They were also given meal breaks.

To the workers, the announcement was treated as a major victory for their campaign.

Also Read: These Laundromat Workers Were Fired After Forming a Union. Now They’re Fighting Back

“The safety committee was very good because before we didn’t have any way to approach the company,” said Escalante. “Right now, thanks to the health and safety committee, any tool we need we tell the company and they provide whatever we need.”

Although the workers won their safety committee, they continued to demand pay increases. The workers say that initially, management agreed to raise wages to $17 an hour in January, but reneged on its promise and refused to negotiate with them. Instead, Escalante alleges that the company resorted to intimidation tactics and has fired three workers since their campaign began.

Best Super Cleaning co-owner Joseph Jacobowitz did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

According to Rosanna Rodríguez, co-executive director of the Laundry Workers Center, a supervisor had told workers that the company would fire anybody who tried to recruit new workers into the campaign.

“They would separate workers discussing organizing with new workers and warned workers not to speak to new workers about the legal case or the organizing campaign,” she said.

Still, Rodríguez said they will continue to organize the workers, saying they are guided by the values of labor leader Cesar Chavez.

“Workers are strong,” said Rodríguez. “We are going to continue fighting for better conditions. We want to call advocates for the immigrant communities, students, labor unions, allies in the labor movement, and the Jewish community to support this group of workers. They are humans seeking a dignified job to provide for their families.”

For Escalante, the campaign is not about him or the workers’ demands but a fight for the dignity of immigrant labor.

“Victory for me looks like giving inspiration to other workers so that they are not victims of retaliation and discrimination.”