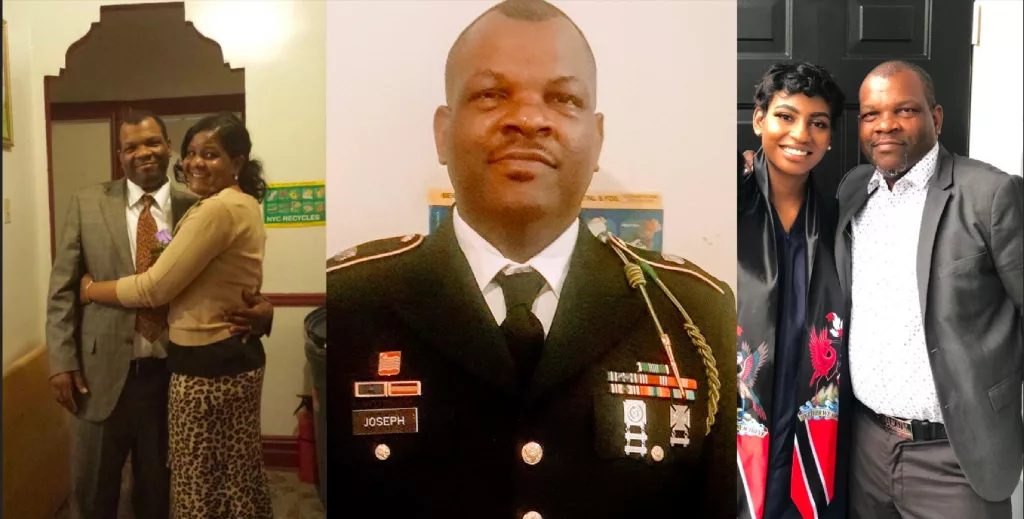

December 1, 2023, would have marked Hilarion Warren Joseph’s first job anniversary as a track worker at MTA. The father of six had struggled for years to find work before securing this job.

He wanted to celebrate in his home country of Trinidad and Tobago, and pay tribute to his mother, who died last year, on Dec. 1. Some of his final words to her had been: “I got the job, Mom,” Warren’s 26-year-old daughter, Jewel Joseph, said.

Hilarion bought his ticket but did not make the trip. Two days before, he was killed by an uptown MTA D train while working on subway tracks as a flagger for a trash cleanup crew on the roadbed near the 34th Street Herald Square station.

The news left his family devastated.

When Jewel Joseph received word on Wednesday morning at around 5:00 a.m., she rushed to Bellevue Hospital, where her father was taken to the emergency room. The MTA accident happened at about 12:13 a.m., and by the time she arrived, Warren’s body had already been taken to the morgue.

“One of our family members is a pastor, and he came over to our house. I was seven years old at the time and he asked my dad, ‘Do you want to get baptized?’ And I said, ‘Well, Daddy, I’m getting baptized with you.’ We both went and got baptized in the tub at our apartment together. And ever since that day, I felt extremely connected to my dad,” said Jewel.

Securing an MTA job had been a triumph for Hilarion after 35 difficult years of living in the United States. He had survived the Gulf War, years in a detention center and addiction on the streets of New York. Shortly after his death, Hilarion was referred to in the media primarily as an MTA worker, but his family and friends remembered his rich and complex life that was marred by the U.S. immigration system.

From the Gulf War to detention

Hilarion Warren Eusta Joseph was born in Siparia, Trinidad and Tobago, on October 21, 1966. He came to the United States on a green card in 1987 and joined the military three months later at the age of 21. In 1990 and 1991, he served in Operation Desert Storm and Operation Desert Shield during the Gulf War, for which he was wounded and received multiple decorations.

Also Read: The MTA Says Immigrant Subway Cleaners are Not Entitled to Prevailing Wages

“I was trained for the first Gulf War in a unit that was a kill-or-be-killed unit,” he said during a speech in 2008 at the Park Avenue Armory. “The focus was to be physically and mentally able to kill. After coming back from the war, I suffered post-traumatic stress disorder, Gulf War syndrome. The government cared very little about myself as well as the other veterans.”

Joseph was honorably discharged in 1997. Left with no rehabilitation and no job after the war, during the speech he said he battled alcoholism and turned to drugs. He also revealed that during that time he attempted suicide four times.

On October 10, 2001, he was convicted of a weapons violation for purchasing a handgun for individuals to whom he owed money. He violated his probation for failing to inform his probation officer that he had moved to his mother’s house and he failed a drug test. For this, he was incarcerated for six months.

After his criminal sentence, Joseph was placed in immigration detention for three years and two months at the Hudson County Correctional Facility in New Jersey. It was there he met Armstrong Agbortabi, a Cameroonian asylum seeker who was incarcerated in September 2001.

Agbortabi described Warren, whom he calls “brother,” as a leader and a man who loved God with all his mind and everything in him. He said Joseph would often refer to his troubled life to teach inmates, especially the young ones, how to improve themselves.

“He was the kind of person who unified and brought people together and looked out for people,” Agbortabi told Documented. “He looked out for immigrants, no matter where they came from.”

At that time, inmates nicknamed Hudson County Correctional Facility the “real United Nations” because “that’s where you met people from all walks of life,” he said.

Immigration detainees shared the same units as other inmates, even those with criminal backgrounds. An immigration section was created in 2002, and Agbortabi and Warren were moved there eventually.

Agbortabi said that Joseph often visited the law library looking for cases that might fit his. They became friends; often praying together and talking about their families. Warren told him how he enrolled in the U.S. Army after arriving in the U.S.

“Without the knowledge of his mom, he had just seen this form about enlisting and filled it out before he knew it; officers came to their house, and that’s how he joined the military the next day; the mother could not stop it,” said Agbortabi.

A veteran unfit for the U.S.

The government initiated removal proceedings, and on July 12, 2004, an immigration judge conducted a hearing. Immigration Lawyer Claudia Slovinsky was his legal representative at the time. “I remember him saying, ‘The U.S. government would bury me in the United States if I were dead, but they won’t let me live here,’ ” Slovinsky said.

Hilarion filed for asylum and became an active member of Families for Freedom, a New York-based nonprofit organization assisting immigrants facing deportation. He used multiple channels to voice his situation and advocated for immigrants, especially those who enrolled in the U.S. Army.

Hector Barajas, a veteran and director and founder of the Deported Veterans Support House, first learned of Hilarion while he was deported to Mexico in 2004. After years of correspondence, Barajas finally met Hilarion in New York in 2019 when Hilarion was working for the New Sanctuary Coalition, a nonprofit that had helped immigrants facing deportation and detention.

“I’ve worked with hundreds of deported veterans or family members, and there’s very few that would start helping others that were in the same situation,” said Barajas of Hilarion’s service. “To find somebody like that, that gets involved with the community and starts helping others that are going through the same situation, that is very rare.”

Hilarion’s story was featured in multiple news outlets, including TIME, The Nation, The New York Times, and Democracy Now!.

Because he was convicted of an aggravated felony, the immigration judge concluded that he was not eligible for asylum. Moreover, he couldn’t naturalize because “the aggravated felony conviction prohibited him from establishing that he has ‘good moral character.’ ”

“We have immigrants who have come to this country and who are giving their lives and putting their lives in the line for American citizens’ children to protect this country and the rights and the beliefs of this country. And then, we are placed in the streets without any help,” he said at the Park Avenue Armory.

Hilarion obtained a grant of cancellation of removal that reinstated his green card and led to his release from detention.

He became a U.S. citizen in October 2016.

“Mr. Joseph was a hero who served his country, not only as a veteran but also as a beloved father and community member who spoke out about the injustices of the U.S. immigration detention and deportation system,” said Alina Das, professor of Clinical Law and NYU School of Law. Das met with Hilarion a couple of years ago as her clinic was collecting stories of people impacted by prolonged immigration detention.

Warren faced many challenges to secure employment after his detention. He worked at Papa John’s, then as a newspaper carrier. He also worked in construction and welding jobs. Relying on word of mouth, he undertook freelance construction jobs such as repairing gates and renovating houses and yards.

He tried to get a job at the post office, and finally, he began working at the MTA as a track worker. On the day of his passing, he was working as an MTA flagger alerting incoming train operators that his crew members were operating on the tracks.

“Sometimes I’m just like, you know, God loves me so much,” said his daughter Jewel. “He gave me my dad, you know, like, he gave me this person to help me get through life. And my dad did.”

Warren Joseph is survived by his wife, Alodia Joseph, 53; his daughters Hilary Koch, 32; Tamieka Holder, 28; Jewel Joseph, 26; Kerry Ann Harry Turner, 24; and his sons Japeri Smith, 24, and Elijah Hilariel Israel Joseph, 5.

Warren Joseph’s funeral (viewing) will be held on Dec. 12 at Carib Funeral Home, 1922 Utica Avenue, Brooklyn. He will be buried the day after at the Calverton National Cemetery in Long Island.