As part of Documented’s new “Our City” interview series, we are speaking to prominent and influential New Yorkers who have deep connections to New York’s immigrant communities, some of whom are immigrants themselves. We ask them about how they made New York City their own, where they feel most connected to in the city, current projects, and more.

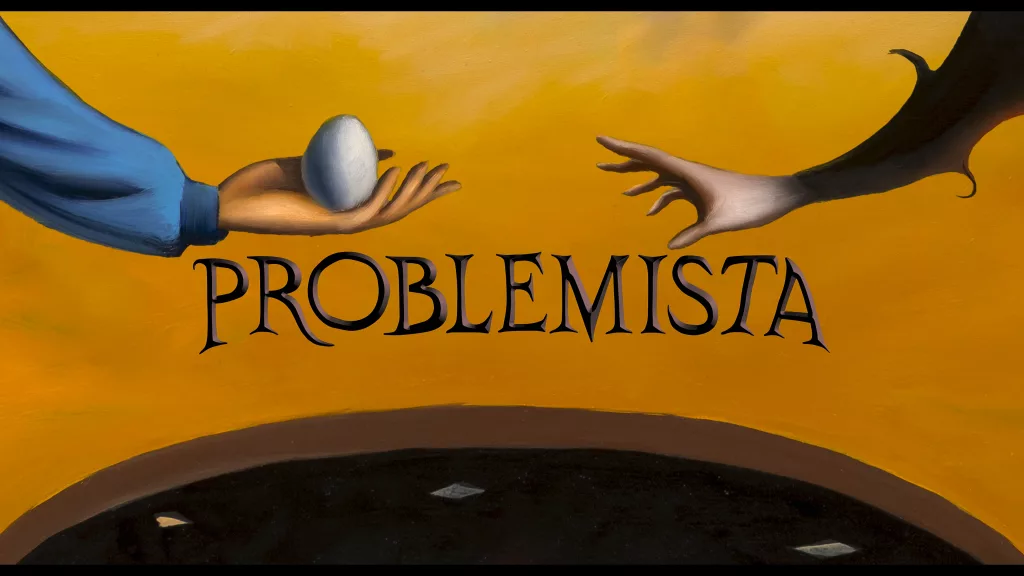

A FEW MINUTES into watching “Problemista,” you will see an illustration of the title briefly appear. Two hands hover above the word “problemista.” One is holding an egg, and the other hand is reaching for that egg from the opposite end. The artwork is the perfect distillation of the sense of striving that is at the heart of the film’s portrayal of the American dream. The film’s premise is simple: Alejandro, an aspiring toy designer originally from El Salvador, is struggling to find a new job in New York before his work visa runs out. The job must also come with a visa sponsor for him.

An irony of Alejandro’s pursuit to get employed by an employer who can ultimately co-sign his visa, can be understood by anyone who has ever tried to get a work visa in the U.S. The more we struggle for the egg to hatch — a representation of our potential and dream — the more we are carried back ceaselessly by obstacles in the immigration system.

The film is loosely based on the life of Julio Torres, the 37-year-old Salvadoran writer and director of “Problemista,” who also plays Alejandro in the film. Featuring an A-list cast — Tilda Swinton, RZA, Greta Lee, Larry Owens, and more — “Problemista” is the latest from Torres, a comedian, who is well-known for his past work on “Saturday Night Live” and “Los Espookys,” a bilingual HBO sitcom. Torres’ approaches comedy from a unique lens. The New York Times, for example, described his past work as “drawing its energy from whimsy and delight [with] an air of guileless and childlike poetry that’s rare…in contemporary comedy.” Indeed, this can be seen in Torres’ current work; his treatment of immigration problems in “Problemista.”

Alejandro’s housemate (played by Spike Einbinder) tells Alejandro that if he indeed runs out of time on his visa, he can just change his IP address so as to pretend he is outside the U.S. — a statement that underscores many people’s ignorance of procedures that non-citizens have to follow to remain in the U.S.

The film is a microcosm of the U.S. immigration industry and capitalist society, filled with satire and comedy. Each scene and dialogue represents something: Alejandro being lost in a bureaucratic maze is depicted in the film with an actual maze. In one scene, someone’s handbag is stuck between two doors on a moving train — a visual representation of the ongoing chaos in Alejandro’s life, but also how chaotic riding the subway in New York City can be.

“Problemista” is a movie I identify with in many ways because after graduating from school in New York City, I too went through that process of struggling to find a job. Like in “Problemista,” where people suddenly vanish when their visa runs out, I too saw my friends, other international students, ‘vanish’ — i.e. relocate to other countries or their native country.

“Problemista” started screening in select theaters March 1, and will screen nationwide starting on March 22. Documented spoke with Julio Torres about how he created the film; chose his friends to play roles in the film; and how this film is really about what he experienced in the U.S. as a new immigrant over a decade ago.

Given Alejandro’s experience is something similar to what you experienced in real life, if you were to put a number behind what percentage of the film was borne out of reality or fiction. What number would that be?

60% true. 40% embellishment.

I would like to think this movie has been in the works — in your mind, before production actually became a reality — since after you graduated from your program at The New School in 2011. Is that correct?

Not that early because I certainly wasn’t thinking about dramatizing my life while I was living it. So, basically, this movie is set during OPT [Optional Practical Training] like in your experience. That, [OPT] happened, and four years went by, and then I went from a work visa to an artist visa. My experience depicted in the movie was roughly 10 years ago. I would say that I started playing with the idea for this movie maybe five years ago.

Is the intention behind creating “Problemista,” representation for people like me and you — who had to go through the hassle of the U.S. immigration process — to see themselves portrayed in a satire so that society can see how ridiculous this process is. Or is the intention corrective in a political way, that is to say the immigration system is ridiculous. Let’s correct that. Or is it both? Or perhaps, none?

In an ideal world, the takeaway would be both. But if I’m being completely honest, that is not what was in my mind when I first opened my laptop and started writing this movie. I felt like I was writing something that was true to me. It is only now doing press, talking to people like you, talking to people who have seen the movie, that I am reminded that the things that we feel very lonely in, are actually relatable and you’re actually surrounded by people going through that, and maybe we just don’t talk about it enough.

I remember going through those experiences, I felt so lonely because I was surrounded by people who were not going through that experience, who were maybe going through struggles that were completely different than mine, and they felt lonely in whatever those struggles were. But no, I didn’t set out to make something that had some grand thesis statement about anything. I think that this is what felt true to me, and it so happens to be resonating with a lot of people.

I have seen a lot of movies that I really love that are about things that I haven’t gone through but touch my humanity. I am lucky that I have never had a parent die. And yeah, I’ve seen movies about that. I feel for them and I empathize with them. And then, when I hear about someone’s parent dying, then I think about those and then I connect with those. So maybe, this [“Problemista”] will make people think about experiences that are not their own. If you have gone through that experience, maybe it’ll make you feel a little less lonely.

“I remember going through those experiences, I felt so lonely because I was surrounded by people who were not going through that experience.”

What insights or lessons did you gain while working on “Problemista,” that you’d still like to explore in more films to come?

I love that question. It reinforced that I love working with friends. And that you don’t have to work with difficult people that you don’t get along with, necessarily to make good work. That making a movie, making a work of art can be pleasurable. There’s a lot of romanticizing the idea that making a movie has to be difficult, and there’s no sleep, and it’s volatile, and there’s egos. I realized, oh, actually, I can do it without all that. And I would love to continue to.

How did you choose which of your friends will play what role in the film?

I did not know Tilda [Swinton]. I was a huge fan of hers, and when I heard she was interested in talking to me about the movie, that was huge. Now, she’s a friend. Now I feel a connection to her no different than a lot of my actor- comedian- performer- writer- friends, who I’ve known for many years.

I also didn’t know RZA or Isabella Rossellini before. But I had a decent admiration for them, and now, I feel like they are like a part of me. The rest of them were actually the smaller parts of the movie like The Bank of America teller, the waiter, the roommates — those are all friends, and I wrote these parts with them in mind. Craigslist — [played by Larry Owens] — those are all friends of mine, who I knew I would have a great time making something with.

There was a scene at the end of the movie where art pieces were shown across different parts of the city — in the subway and other places. That, to me, was a representation of how we leave parts of ourselves — or experience growth — across every obstacle we face in life.

Yes.

It also truly felt like an opportunity to help showcase the work of artists in the city, given you created “Problemista,” as a monument to all artists who pursue something, and find that thing, in spite of all the problems they encounter in life. Were those art pieces/objects the work of an actual artist or just props in the movie?

They were commissioned and made by a friend of mine, who’s a welder, and an artist, and they were specifically made for that sequence. Now, I have them all crammed in my apartment.

“Working on “Problemista” reinforced that I love working with friends. And that you don’t have to work with difficult people that you don’t get along with, necessarily to make good work.”

You’ve now lived in the U.S. for more than a decade. Where in the city do you feel most connected to?

I actually love riding the subway, like people hate it, I still feel like I’m going on a little adventure. And I still love it. I still feel a sense of accomplishment using the subway. It’s like “oh look at me, I can figure out this very difficult system.” Because I wasn’t raised here, it was intimidating at one point, learning how to use the subway, and now it isn’t. Now it’s sort of second nature. That, and also just the areas that are depicted in the movie. The areas in Bushwick, the intersection between Myrtle Avenue and Broadway feel very familiar to me.

After moving to New York City, at what point did New York become home for you? How did it become yours or authentic to you?

I had a very long time feeling settled here for many reasons. Like you pointed out, I’ve been in New York for 13 years but maybe like half of those were me trying to figure out if I was going to be able to stay here. And like everything, I felt like I was building a house of cards. I had an apartment, but I didn’t know for how long. I had a job, and I didn’t know for how long. I didn’t know where the next check was gonna come from and all those things. And yet, even though it felt like the city was pushing me away, I found that I made friends fairly quickly. I felt pretty embraced very early on. I think specifically, when I started doing stand up comedy, and I started meeting other people like me that were interested in what I was doing, then I started feeling like I was home.

When you think about yourself in New York, do you think of yourself first as a Salvadoran immigrant in the City or as a New Yorker?

I think both. I feel like the implication of being a New Yorker, there’s like a sense of ownership over the city that comes with that term. I feel at home, but I don’t feel like it’s mine. I feel at home, but I don’t feel like I own it, or can dictate what happens in it. I feel like I am one of many little animals in the ecosystem. Like I can tell you where the trash is supposed to go.

When you moved to New York in 2009, what were your first days in the city like and what was a culture shock for you when you first moved that still stands out to you today?

So much of my first year was dedicated to figuring out how to live and operate here. By that, I mean figuring out how to get a cell phone, figuring out how to get a bank account; all those little things. What I was really struck by is how difficult all of those things were. All of them required something that I didn’t have. It’s like you want a phone, while you need credit to get the phone. I ended up getting like a burner phone at like a Duane Reade or CVS. Those would charge me 50 cents for every text I got or received. So if someone texted me “okay,” I was out of 50 cents. So I would buy like $5 cards. I was struck by how hard the little things that in El Salvador I took for granted were. And it was a lot of that. A lot of learning that you have to be so vigilant because the less you have, the more is asked of you. That I think is why that “Bank of America” scene is in the movie, because it is very expensive to not have money in New York City.

The Bank of America scene. I was trying to remember who shot who in the movie. Did Estefani, the Bank of America teller, shoot Alejandro or did he shoot her?

She shot me.

I recognize that as dark humor, it’s also a fitting depiction of how the capitalist system in the U.S. attempts to stifle you to death.