As part of Documented’s new “Our City” interview series, we are speaking to prominent and influential New Yorkers who have deep connections to New York’s immigrant communities, some of whom are immigrants themselves. We ask them about how they made New York City their own, where they feel most connected to in the city, current projects, and more.

AS A LITTLE KID growing up, Michael Lee spent his days at his grandfather’s apartment at 78 Mulberry St. in Manhattan’s Chinatown. As with many of the tenement apartments built during the turn of the century, and where many Chinese immigrants lived, the apartment was small. The bathtub resided underneath the kitchen counter. Once the counter was off, his grandfather would hook up a hose to the kitchen sink, and snake the hose into the tub. His grandfather took care of him, his brother, and cousins in this apartment while Lee’s parents went off to work at their professional jobs. That was Lee’s daycare.

“I thought it was great, because I was a little kid. I didn’t know anything,” Lee tells me. “Looking back on it, it definitely was a rougher way of life. I definitely don’t know how often my grandparents took baths, unfortunately.”

While Lee, 44 years old, frequented Chinatown as a kid and in his older adult life, his parents lived in Carroll Gardens, Brooklyn, where he grew up and where he now lives with his wife and three children. He later went to prestigious institutions, New York University and University of Pennsylvania; worked for the New York Institute of Finance as the Managing Director of Corporate Development, served as the Executive Director of Apex for Youth, and serves on the board of directors of the Chinese American Planning Council (CPC), Central Queens Academy Charter School, and the Red Hook Initiative.

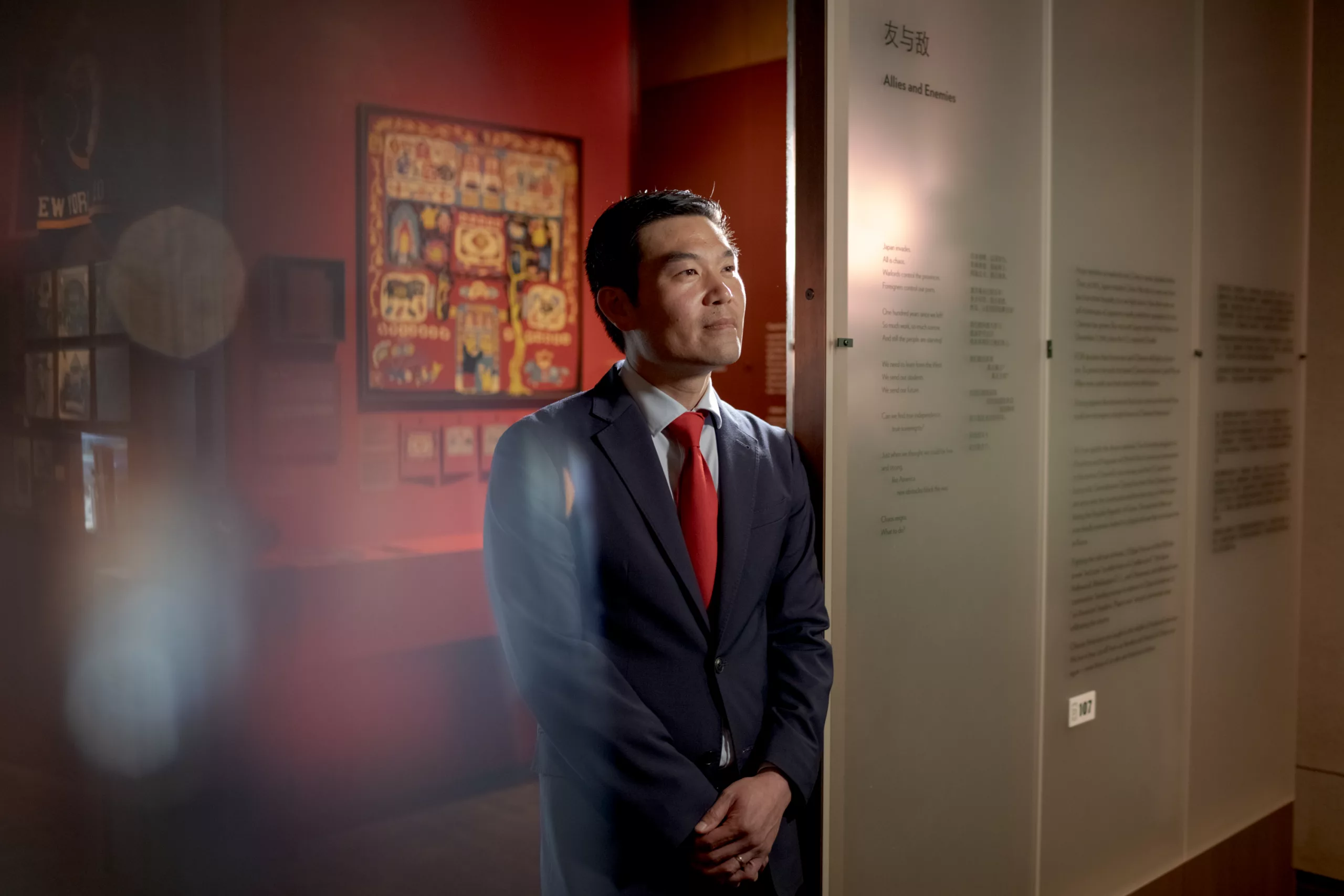

In April, he added a new role under his belt: President of the Museum of Chinese in America.

Also Read: The Museum of Chinese in America Makes the Case for Celebrating AAPI Heritage Month

Before his interview for the role to be MOCA’s President, Lee asked an educator to take him on a tour of the museum. Clever, to say the least. Having now spent just two months in his new role, already, Lee knows every nook and cranny of the museum which sits on 215 Centre Street in Manhattan’s Chinatown.

MOCA, founded in 1980, has become a major character in Chinatown, the bearer of many facets of Chinese American history and the subject of a controversy that has become an intriguing narrative on its own.

In 2021, MOCA accepted a $35 million grant from the New York City government because it needed money to purchase its building. But many Chinese residents in Chinatown got angry at MOCA for collecting the grant, reasoning that the city gave it to MOCA so that Chinese residents would be more accepting of having a jail complex built in Chinatown. Since then, MOCA has resisted those criticisms, and this year, used the $35 million grant from the city to finally purchase the six floors of its building — one of those floors, several years ago, housed the record label Interscope Records.

That controversy precedes Michael Lee’s presidency. And he’s undeterred by it. Lee is now involved with overseeing the transformation of the modest two-floor museum into a modern six-floor structure that would represent more Chinese ethnicities than it currently does.

The building must still be renovated and brought up to code — whether that will happen by pulling down the whole structure or renovating it in bits, Lee isn’t sure yet. (In 2022, the renovation plans for the Museum of Chinese in America were estimated to cost $118 million.)

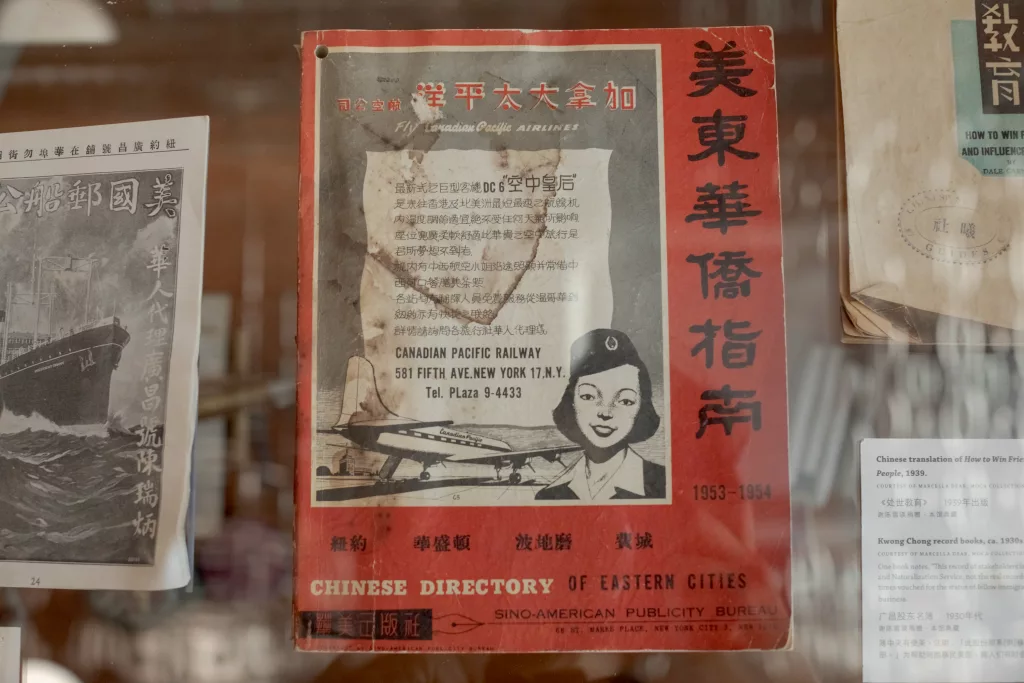

As we tour the museum, Lee walks me past a picture on the wall that he suspects includes one of his grandfathers, both of whom served in the U.S. army. While Lee was born and raised in New York, he says he sees himself a lot in MOCA’s exhibits because he sees the way his grandfathers immigrated here, served in the U.S. military, then brought their wives over for the War Brides Act. Lee’s grandparents migrated from Southern China, Toisan to be exact, which is one of the first villages that settled in the Chinatown communities in the U.S. owing to the fact that immigration from China in the 1800s was initially based off of trade, which came from southern China through boats.

“My whole arc is listed there,” Lee tells me. “But if my parents got here in the ‘70s as scientists and we grew up in the suburbs, and we contributed to America in a different way, then, obviously, I wouldn’t see myself as much in the exhibits.”

Sitting opposite me at MOCA’s reception area, answering questions about his family’s migration story, his plans for MOCA, and enduring questions about the controversy that preceded his presidency, Lee is calm.

“We want it to be more expansive,” Lee says. “We want to show a greater diversity of different stories of Chinese here in America. There was a huge wave of immigration after the 1960s. Highlighting and emphasizing those folks from that generation is key.”

You resumed work at MOCA in April. How have the first couple of months been for you?

Every day is a new adventure, and it’s definitely getting the blood flowing. Sometimes you have interviews, sometimes you’re throwing fundraisers, sometimes you’re working with kids in their workshops. You just throw yourself in and do the best you can.

I’m curious why you accepted to be MOCA’s president.

Originally, I got involved with the job because a lot of the board members that were part of my old nonprofit actually became trustees here. When they said this position was open, I looked at the job description and I said, alright, well, let me see what happens. So I applied.

It was like a seven-month interview process because it was going through a search firm, and obviously anytime you interview for a president job, then you’re working with a subset of the trustees. So it’s not just one person determining whether you get hired or not.

Through all those interviews, thinking about the job more, thinking about coming back to the community [having, five years ago, frequented Chinatown a lot while working for Apex For Youth] and the prospect that they were close to closing on the building, really excited me.

They offered me the position on a Monday, and they actually closed on the building on a Wednesday.

This idea of having an institution that will last here longer than ourselves is really something that can add to one’s legacy. When you think about a legacy and how you want to change the world, this would be a great thing to leave behind.

If my grandkids can come here one day, that would be an amazing feat. Just knowing all the children that can come in here through the years is too. This resource wasn’t as big when I was a kid and didn’t have as much exposure. So, if we’re able to open it up to a lot more children that’s going to play a huge role in informing more people about the history of Chinese in America and its people and its culture.

Nice. When MOCA acquired the building earlier in the year, that was made possible because of the $35 million grant from the City, correct?

Yes.

You were deeply aware that the grant led to a controversy and protests over the past few years. Did that sort of scare you a little bit, knowing that you’re going to be the president, there’s this whole thing that happened prior to you joining, and you would have to deal with that when you join?

Public relations is not one of the things I would have a huge amount of experience in other than building relationships in the community. Speaking out to the media, trying to answer questions like this definitely was out of my comfort zone. But as I got the position, started prepping for the media, started talking with more people and becoming more comfortable, it’s something that I feel right now is part of the territory. Hopefully, in the future, we’ll be able to move past this, and then the museum will continue to build.

Did you have any concerns?

Of course, I had concerns because you always have concerns about people that are trying to — kind of, I mean, basically, I’ll put it flat out — denigrate you in public. But at the same time, you start to compartmentalize and realize, Okay, well, is it the entire public that’s against the institution and against me, or is it, just some folks that have a certain ideal about it?

As I was getting out there in the community and started reconnecting with a lot of people that I used to know, everybody was really supportive. Yes, we certainly have detractors here at the museum and they feel a certain way I guess because of the investment, but at the same time, the vast majority of people that I speak with want to see this place succeed and want to see me in this leadership position succeed. That’s been really encouraging and I lean more on that and building the museum through that rather than focusing on the detractors.

“If my grandkids can come here one day, that would be an amazing feat. Just knowing all the children that can come in here through the years is too.”

Considering these critics have their own vision, what do you think MOCA’s ideal should be as you herald its new phase? Part of the reason people protest is because they believe the institution once served the working class and now targets a different audience.

We want all audiences to feel like they have a place at the museum. Whether you’re coming strictly from the community or the working class or your family came here and then moved into the middle class or upper class, we want everybody to see themselves here in the exhibits, and here in the museum, especially the Chinese in America.

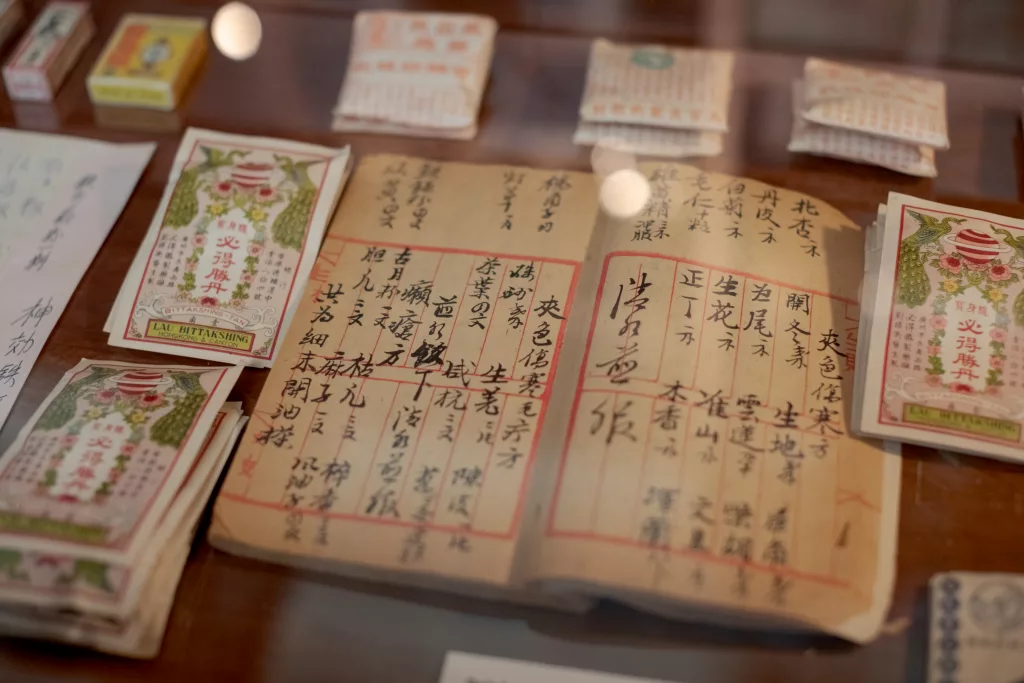

In our exhibits right now, we’re very focused on the past. That usually lends itself to one kind of ethnicity in the Chinese race, which is the southern Chinese, which was a lot of what constituted Chinatown before.

But now, Chinese in America are very vast and diverse. You’ll have Chinese from Northern China here, Chinese from Taiwan, Chinese from all sorts of different regions of the country. They all got here in a much different way. Some of them are here to study, some came here because their parents were here to study. Their stories are much different than what you see in our exhibits now. It’s our job to make everybody feel welcome and for the Chinese in America to see themselves here in the museum.

In terms of the clientele that comes here, I want everybody to come here, especially youth and families from outside of the Chinese community because then they can see all the disparate stories that we have out there. We’re not just a monolith. We have different routes on how we got to the country and different ways that we’ve contributed along the way.

In addition, even past the exhibits and past the building, we want MOCA to be somewhat like a media company and to be able to broadcast our stories out there in different ways. So whether that’s through social media, or from podcasts, books, blogs, and film. If we can broadcast our stories out there, maybe we can do it at a faster rate, and also be able to tell greater diversity than just what you can fit on a wall.

“My own personal way that I work is really developing a clarity of message, allowing people to really feel and understand what the organization is doing.”

How does the museum plan to use the grant to benefit the Chinese or AAPI community?

The grant was given by the city directly to the seller of this building. So the museum never actually officially held on to the grant at all. The grant is used to benefit the community by having this building permanently be here, dedicated to telling stories of the history of Chinese in America and its people.

The city also put a stipulation here that MOCA can’t sell the building for 30 years. So it’s going to be dedicated to our mission. For those that are motivated to see us liquidate the building, that’s not possible.

So you guys are here for life.

Pretty much. That’s the plan.

Do you sometimes feel like this project is bigger than you?

Yes, sometimes it feels surreal. I’ve never really renovated a whole building or built such a project or building from the ground up.

You hold a position shared by many leaders: the responsibility of growing an organization and team you represent, while also striving to add value to others. As a leader, how do you manage to keep everything together, given how frequently organizations tend to unravel? What insights do you have about communication and negotiation that maybe other leaders might currently be missing?

Well, I don’t want to criticize other leaders but in my own personal way that I work is really developing a clarity of message, allowing people to really feel and understand what the organization is doing. If you can make a clear message and it’s repeatable by people, then they can go out and be advocates for you as well.

That being said, also be an advocate for yourself and get out there and build as many friends as you can, that’s how you build an organization, you have to build a little army of supporters in order for things to grow.

Some of those supporters may be big or small, but you have to just keep going out there and building relationships. You never know where one relationship is going to lead to help your organization to advance.

Do you think you are able to do it in a way that genuinely benefits people and not just superficially or apparently?

That’s on our staff to be able to generate great programming and opportunities for other people that might not be donors necessarily. Like little kids and maybe senior citizens. To provide access for the museum to them and allow them to give their feedback and participate. Yes, in a sense, you are making relationships with supporters that may be supporting you financially, but then that translates into having a great staff that is creating welcoming environments for all. I think that’s where the translation happens.

A recent New York Times article announcing your new role, indicated that you hope to perhaps meet activists and hear them out, given that for the past three years activists have been so consistent in their protest against MOCA. In what ways do you think a conversation with them will enable you both to come to terms?

I don’t necessarily know if a conversation will allow us to come to terms. The entire time that I’ve been here two months, no one’s asked me to actually come and talk. It is more of just kind of heckling me and saying shame on me. I’m always wanting to talk with anybody. But at this point, I’m not sure what the motivation is, if it is to talk with me, then they have it at any time. But there might be some other motive that they have in order to be protesting at the usual times that they do.

Is Jonathan Chu still part of the board? [Editor’s Note: Chu is a commercial developer and heir to a Chinatown real estate dynasty, and viewed by some as accelerating gentrification in the area.]

Jonathan is still part of the board, yes.

Some critics have said MOCA needs a new board because the same board means the same problems. Does it appear that the controversy made some people — who might not even be protesting — start distrusting the institution? Is it part of MOCA’s plans right now to focus on rebuilding trust? And, as part of that focus — if there is — will changes be made to the board?

We absolutely want to rebuild trust. We want people to know that this is an institution dedicated to its mission, and that the mission is the focus. And that’s what everybody on the board is only focused on. There’s no ulterior motives out there. In terms of rebuilding the board, I believe 80% of the board is different from maybe two or three years ago. The majority of the board is different. I think it’s more of we need to build the relationships again, and let people know that they’re all welcome here at the museum.

How has MOCA been recovering from the big fire that affected some of its artwork at the beginning of the pandemic, or have you guys fully recovered?

We saved 95% of the artifacts from the facility over there. Now, we have them in our collections unit, which is around the corner from the building. Getting some of the generous grants that community members gave us allowed us to take a step back, look at our collection, survey it, see what we had, restore it properly and what needed to be stored in the right way. We’ve had consultants coming in and teaching us the proper way of storing all of our artifacts and cataloging them. We also received a very generous grant from the Mellon Foundation to survey all of our items. We found out 75% of them probably need some sort of restoration work. But we’ll continue to keep restoring items as the funding comes in to allow us to do so. They’re not going to deteriorate, but they just need a little bit of work in order to be display worthy.

I wonder if you frequented MOCA back when you were younger and how’d you say the museum has changed overtime?

I didn’t. I should have a lot more. My parents were working all the time, they really didn’t take us to a lot of cultural institutions, they rested mostly on the weekends. I know my school never visited, and we [MOCA] weren’t in this larger location that it is now. We were actually in the public school that my father went to on Mulberry Street. MOCA was smaller back then than the more expansive space you see now.

I’m really thankful that we have this type of space because schools can find us easily. This last May was Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Heritage Month, so we had two or three schools tour in here every day, allowing students to learn more about Asian Americans and history here in the country.

Is the museum planning any major projects or exhibitions for the summer?

For summer, we’re going to have a dragon boat fest where families can learn about the culture of Dragon Boat Racing, why it was such a big deal not only in China and in Hong Kong, but also here in the United States. In the fall, we’ll have a new exhibit based on Asian American magazines that were published from the 1970s to the early 2000s, and from their publications, you can see the formation of Asian American cultures.

You commute to MOCA on the train and, as you mentioned, you are a life-long F-train rider. Has something weird or interesting ever happened to you on New York City’s subway?

I mean, weird things happen every day. One time I fell asleep on the subway and ended up all the way in Coney Island. I read that there were these people called lush workers, and they’ll actually take a razor blade and cut your pants open, and then be able to get your wallet. That actually happened to me once.

Oh no.

I went all the way from Columbia on the 2 or 3 to the F, and I fell asleep. I ended up in Coney Island. Then, I felt a breeze on my leg and noticed my wallet was gone. But you know, I mean, I was completely asleep at the time. So I didn’t feel like I was a victim or anything like that. It just happened, then I looked in the New York Times, and there was an article about how skilled these people are. And they’ve been doing it for many years.

How long ago was this?

This was probably in my 20s. So, 20 years ago.

“The person that I was at my previous job, running that business [at the New York Institute of Finance], is different from the identity that I have to assume here at the museum.”

Do you have a favorite restaurant in Chinatown?

The one that brings back the most memories right now is Hop Lee. That’s where we always have our family gatherings or unfortunately, whenever people pass away, then we would always go there. Later in my life, I joined a Chinatown Rotary Club, and we would always have lunch at Hop Lee. In terms of other Chinatown food, tough to say. But we’ve been going to August Gatherings a lot since I came here to the museum. I think they have some really interesting dishes there.

I’m curious how you perceive your identity at 44 years old. Do you feel it’s set in stone, or are you still having experiences that shape who you are?

It’s fixed in the fact that I’m never going to change being ethnically Chinese, or change the fact that I grew up here in New York City, or that I’ve always lived in Brooklyn.

But your identity changes a lot as you start getting older. Once you have a child, I think that’s a real time where you start feeling a huge sense of responsibility, taking care of your family and thinking about them a lot. You start assuming different identities as you play different roles.

This year, before I took this museum job, I actually had been teaching at my kids’ school, and I’d been teaching a class of 8th through 10th graders. So to assume that role of being a teacher every day for a class of students, you start realizing, wow, you can be a very different person. Then the person that I was at my previous job, running that business [at the New York Institute of Finance], is different from the identity that I have to assume here at the museum.

In what way?

I’m doing a lot more media now, and so I have to represent not only myself, but this institution as well. When you start adding on that level of responsibility, then yeah, your identity does shift a bit. You have to kind of push the boundaries and do things that you would not normally do in your comfort zone.

This interview has been edited for clarity and concision.

Do you know who should be in the next Our City? Email earlyarrival@documentedny.com.