As part of Documented’s “Our City” interview series, we are speaking to prominent and influential New Yorkers who have deep connections to New York’s immigrant communities, some of whom are immigrants themselves. We ask them about how they made New York City their own, where they feel most connected to in the city, current projects, and more.

THERE’S A LINE FROM the film “The Vow” that randomly came to mind when I was drafting the intro for this piece. It says each one of us has “our own personal greatest hits of memories that we play and replay in our minds over and over again.”

For Arian Moayed, ‘Stewy Hosseini’ on “Succession,” one of his personal greatest hits of memories was during the time he was growing up in Iran, before moving to the U.S. at 5 years old with his family.

In the basement of their home, they had a korsí — a low table, draped with blankets, under which a heat source is placed and everyone gathers around to keep their feet warm during winter. It is a centuries-old Iranian tradition. Moayed would nestle into the korsí, moving around everyone’s feet, especially relishing the fact that his mom was ticklish. Reflecting on this time, Moayed tells me he was, perhaps unconsciously, trying to make everyone around him feel good by trying to bring smiles and laughter. Indeed, this portion of my conversation with him also stands out to me as the makings of a life leaning toward entertainment, born from a childlike impulse to lighten the mood during a difficult time. “The memories are all very precious, and I keep a hold unto them,” Moayed says. “But they’re all chock full of fear.”

As a young child, he didn’t fully grasp that this basement was, in essence, a makeshift bomb shelter that became a frequent refuge. His family would discuss the Iranian Revolution and the subsequent period, which intensified with the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s, but not the fullness of it around him. During that time, one of his brothers was fighting in the Iran-Iraq war. His sister was protesting in the streets. His father was fired. His family was not politically aligned with the status quo.

In 1986, they migrated to Glenview, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, where his parents enrolled him in school. There were no English-as-a-Second-Language classes for Iranians. Moayed, a Persian speaker, was placed in an ESL class for Spanish-speakers in his first year. At the end of the day, while his three older siblings were either elsewhere in Chicago, in Iran, or studying in medical school, he was at home with his parents, 6 years old, helping to translate phone calls and conversations.

He graduated from Glenbrook South High School in Glenview, and went on to study theater, drama, and Persian studies at Indiana University Bloomington. He met and befriended Tom Ridgely, and together they moved to New York to figure out their vision; Moayed was 22, and alongside Ridgely, penniless, both bursting with potential energy and a determination to create. They eventually co-founded a nonprofit, Waterwell, an organization that brings together artists, educators and producers dedicated to impactful storytelling.

Moayed and I sat in Waterwell’s office in midtown Manhattan for this interview. His little part of the office is decorated with posters from his childhood bedroom as well as photos of his wife and two daughters. On the window sill are several award plaques and trophies.

One award in their midst, belonging not to him but to Shervin Hajipour, stands out. Hajipour is an Iranian singer-songwriter who wrote a song called “Baraye” that became the anthem of the Iranian protests of 2022, driven by widespread frustration with authoritarian rule, human rights abuses, economic hardship, and demands for greater personal freedoms, particularly for women. During that time, Moayed worked alongside celebrities and activists including Nazanin Bionadi and Malala Yousafzai to amplify the fight against the ruling government. Hajipour won an award for “Baraye,” but he was imprisoned in Iran and couldn’t make it. Moayed accepted it on his behalf.

“He and I are friends, and I’ve been like, when you get here, I have your award for you,” Moayed told me. “I’m going to leave it here and tell everyone this is your award.”

Now 44 years old, Moayed has several award wins and nominations to his name including the Tonys, Emmys and SAG Awards. His life story — from being born in Tehran during one of the most turbulent and war-torn periods in Iran’s modern history, to becoming a Hollywood star — is a journey he believes not even a propaganda film about the American Dream could have envisioned. Despite being born and raised in a time where he and his family could have been killed, Moayed, buoyed by love and support from family, pursued a theater and acting career, defying expectations.

Beyond “Succession,” Moayed has acted in other audience’ favorites including “Inventing Anna” and “You Hurt My Feelings.”

I wonder how your personality comes through in your work. For instance, in “You Hurt My Feelings,” your character, Mark, found it hard to accept the truth. And in “Succession,” your character, Stewy, found it easy to tell the truth and be straightforward. Which one do you think you’re closer to in real life?

I’m more of a truth teller. I really just give it how it is. I do that with an Iranian spin of kindness so I’m not hurting anyone’s feelings.

The truth is something that I’m very fascinated with, especially in a time where there’s a lot of post-truth or instances where people describe the truth differently or say “it’s their opinion.” I find that the truth truly is the easiest way to put stuff out there. After our first performance of “The Ford Hill Project” this October, two women guest speakers talked about sexual abuse that women often times throw away in their forms: micro, macro, both of those. [One said that] hearing women speak that truth not only feels — I’m gonna get emotional — like it’s a relief but you can literally see the baggage taken off their shoulders. She said we live in a society, here definitely and elsewhere, where the truth is something that’s hidden, whether it’s family or societal. Your family says “don’t talk about that,” or something of sorts. My Iranian family has many of those; I’m sure a lot of families do. So in a way, I feel we can have more forward progress by actually just dumping the truth out quicker.

I listened to a podcast you did a while back. In it, you said you and your siblings once asked your mom about her favorite memory of Iran and her response was just “Omid.” Your brother’s name. That was funny.

[Laughs] We still say that.

Do you remember what was going through your mind – I know this was a long time ago and you were only five — when your family had to leave Iran for Chicago?

At the time, because we were leaving and not coming back — and it happens today as well in many countries — you can’t bring all your luggage. You pack like you’re going on vacation.

The specifics of it are always so fuzzy. But one thing I just remember is all of my toys were in Iran, and my parents having to be like, “Don’t worry, we’re gonna get them for you.” Then, I was like seven and I’d be like, “Where are my toys?” And they are like “We’re gonna get them for you.” Eight, and same thing. Then at age nine or 10, you’re like, “I’m not getting those toys back.” I’m not shitting on my parents…

It was perhaps difficult to explain it to a child.

Of course. Also, they don’t know the answer. That’s another thing that I think people don’t realize about immigrants. They don’t know the next steps. It is a crapshoot.

How did we end up in Chicago? Seriously, it’s because my aunt went to Chicago in 1971, the only place she’s ever been to, and my brother applied to only colleges in Chicago. Amir, my oldest brother, came in ‘76, which is how I’m even talking to you because by the time all the other stuff happened, he became a citizen and then we came over.

I will say that my parents, when we got here, it was immediately clear that this society was going to give us more opportunities than Iran. My parents were pretty progressive and forward thinking. The idea of going back to restrictions, in light of a culture that’s so open and free culturally, we knew it wasn’t going to work.

“I feel we can have more forward progress by actually just dumping the truth out quicker.”

My parents were married at an ungodly young age. They had children at an ungodly young age. My mom barely went to school. So we got here, and all of a sudden, had to learn English. Then nobody was home; my brother was gone, my other brother, who came back from the Iran-Iraq war, went to medical school. My sister was in Iran. When we came over, it was my brother Omid, who had just finished fighting in the Iran-Iraq war, myself, my dad and mom. My sister had just gotten married during that whole kerfuffle [laughs]. The idea was that we’re gonna come and then they’ll come over as soon as possible but it took 17 years after that.

That’s tough. Is there an earliest childhood memory of being in the U.S. that stands out in your mind?

One day — I’m laughing but this is horrific — there was an auditorium in school, people were gonna come in and we were gonna watch the NASA Space Shuttle Challenger launch into space. I don’t even know what the hell is going on. I don’t know English. [Having been put in an ESL class for Spanish speakers,] I don’t know Spanish. We’re going to the auditorium. I guess it’s movie time. I have no idea what’s going on. The TV comes on, it’s a big screen for a five, six year old. I’m laughing. It’s not funny.

And then it exploded in the air on live television. The NASA shuttle. Everyone in the country was watching it live and then it exploded. And they all died. And then all of a sudden, you could see a panic of people around you being like, Oh my God, holy shit, cries, tears.

I have legitimately no idea what’s happening. I don’t know what this movie is. I don’t know why everyone’s crying.

[Laughs] I can’t believe we’re both laughing at this. Truly a nightmare. So, on your end, you didn’t understand what was happening because of the language barrier, and you were just confused.

It was language barrier. It was confusion. I’ve never been into a room where a big TV is pulled or is showing a movie at school. It was all new. Much later in the evening, my parents were like, did you hear about the thing? And I was like I saw it [Laughs]. The whole school saw it [Laughs].

Hmmm.

There are a lot of memories. The neighborhood we grew up in, imagine going to a grocery store, no English skills, and you have like 55,000 cereal boxes. It’s overpowering how little we know. Just like if you and I went to the middle of nowhere, say in China, it would be difficult to integrate into society.

Also, the fear that was in Iran transferred to a new fear that was in the United States. Iran was so hated. So there was a new fear of, like, ‘Don’t say you’re Iranian.’ There was a lot of that kind of energy. I’m bringing up these memories mostly because I think what was happening to me and probably everyone that’s gone through a traumatic experience that’s happening right now in our streets in New York City is that one fear compounds to another fear and then now all of a sudden, there’s a third fear like, ‘How am I going to make it now I’m here? How the hell is this going to work?’ Along the way, everything just was a compounding of like, oh, holy shit, fear.

I can smile about those memories sometimes because I found an opportunity as an artist to lessen the fear by making my dad laugh, by watching shows and imitating characters I see. I’m saying this as a 44-year-old man looking back at that. I wasn’t consciously doing it. I’m now just like, oh man, that was what was happening.

At the library, you get free movies and the movies that my parents would watch were movies they grew up with and loved: Charlie Chaplin, Lauren Van Hardy, black and white, Sydney Poitier, you know, old movies. No kid wants to watch a black and white movie but watching my mom and dad laughing at Charlie Chaplin made me go into my bedroom and try to mimic falling as a joke. My mom and dad were laughing so hysterically when he fell into the water, I was like that’s so funny, I can do that.

You made “The Courtroom,” a film based on the true life story of a woman facing deportation proceedings, in part because of your mom’s reaction to seeing Trump’s Family Separation policy play out on TV. Has she now seen it?

She has seen the movie, and immediately I knew that it was going to be a lot — I’m going to cry — it was going to be a lot harder for her, because that woman, Elizabeth Keathley, is my mom. I mean, we didn’t have that scenario but the amount of times where I could see a pressure point and her being like, ‘I can’t move forward.’

Something happened at the grocery store growing up, and my mom was crying in the car. She was like, “sometimes when I get a lot of pressure, I forget every English word.” And I get that. I get that loud and clear.

When I was reading the transcripts of “The Courtroom,” that very distinct section where it says, “Would you like a tissue?” it dawned on me that this woman is having a nervous breakdown at a death penalty sentence. When my mom saw that part in “The Courtroom,” it comes home so real too.

I can imagine.

Asides from “The Courtroom,” “The Ford Hill Project,” a play about sexual harassment allegations against two U.S. Supreme Court justices, is the second court-transcript-to-stage-play performance I’ve seen Waterwell produce. It’s a thought-provoking way of making a play. I don’t know if it’s because I wasn’t familiar with that method of creating a play from court transcripts. Is that something that typically happens?

No, it’s incredibly rare. It needs mercy. It needs you to be cool with something that’s not gonna fit directly into your POV, and that’s tough.

What do you mean by ‘not gonna fit directly into your POV?’

There are many moments in “The Ford Hill Project” where these two beautiful male actors, who reenact the two supreme court justices’ roles, are trying to embody empathy in those speeches in which the justices talk about “women that have backed me.”

Their job as artists is to humanize that moment as best as they can, whether it’s manipulative or not manipulative. As artists, it’s very easy for us not to have made that moment where Brett Kavanaugh is talking, crying almost, about 65 women who knew him in high school, who wrote a letter in one night, 35 years after graduation, to say he always treated them with dignity and respect. It’s very easy and kind of simple for us to make a whole buffoonery of him at that moment. We could have made it a whole comedy bit.

Yet, you didn’t. But, people still laughed during that bit, particularly when the actor performing Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s lines said “65 women…in a fraught and ugly situation where they knew that they’d be vilified if they defended me. Think about that. They put themselves on the line for me. Those are some awesome women. And I love all of them.” The audience laughed.

Yeah, and that’s not as a result of my opinion. You can cry. You could.

Same with “The Courtroom.” At the end of the day, this woman who had every intention of doing the right thing did not do the right thing. She acted against the law. We can talk about how fucked up and crazy that is. But at the end of the day, you can watch “The Courtroom,” and you can say, ‘Sorry buddy, you shouldn’t have done that. You got the raw end of the stick.’ Yeah, you can do that.

Someone who was a part of the audience on that day was Hannah Pennington, Deputy Chief for Gender-Based Violence Policy at the Manhattan DA’s Office, and she said during the post-performance talk that “So much of what we saw tonight is how things unfold in less historic but equally pivotal moments.” I couldn’t agree more.

This made me think of something Jon Blitzer said to me recently “You can live your life and escape a lot of the historical resonances even if you’re affected by them. But to live with a kind of deliberateness of choosing not to run away from the past, but grapple with it, is a moral choice.” It makes me wonder if you ever thought that this job you do is, in some ways, a higher calling?

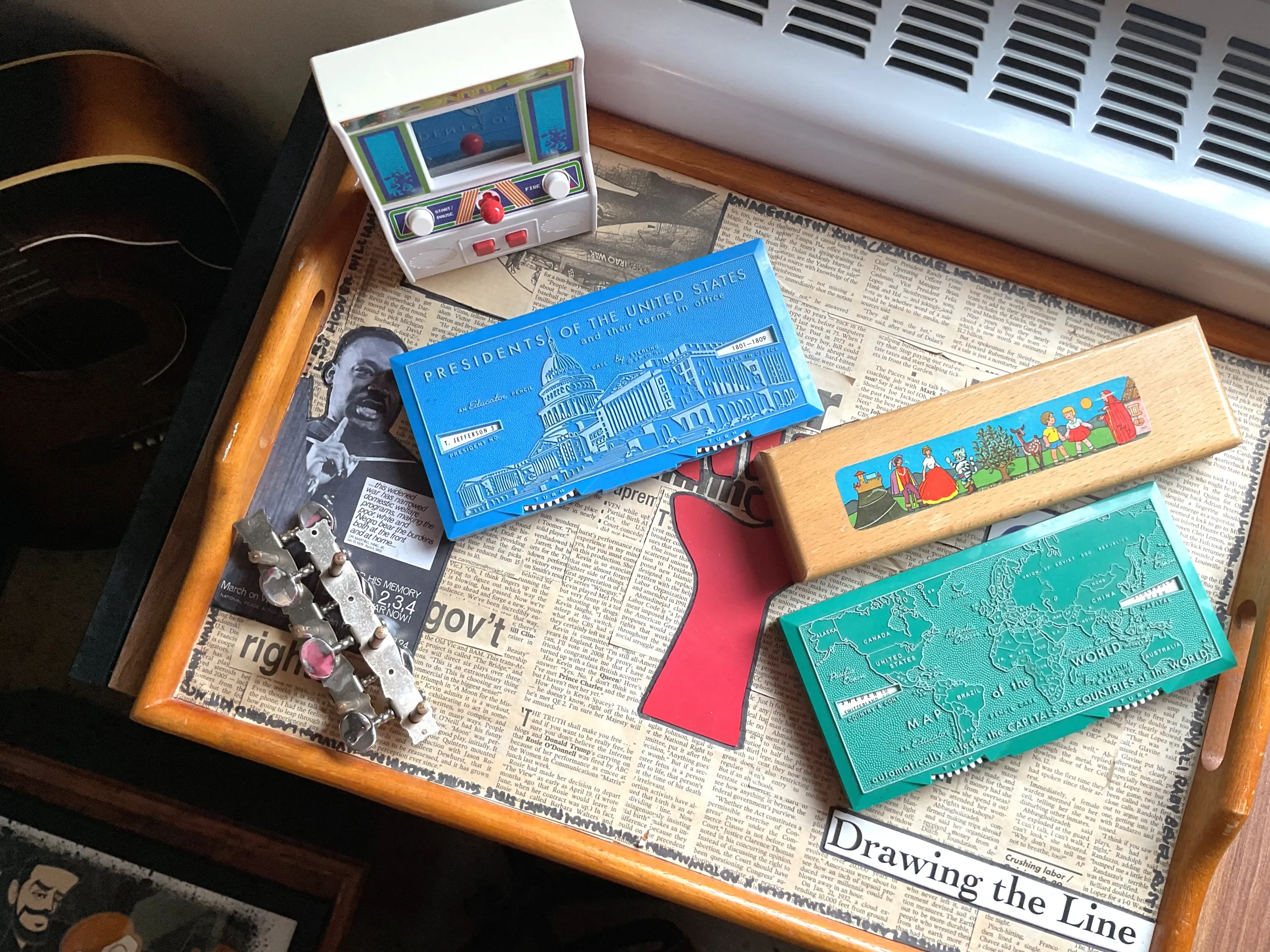

Woah. Yeah, yeah. I do think that. I think there’s a picture I always think about with this. These are musicians and jugglers in Tehran.

Whenever I look at this, I always think I am this guy or this guy right here. I do think it is in my cloth, and that this is part of my heritage, and I think it goes from the beginning of time. I do think it is a calling. And I think it’s a miracle I’m talking to you. It really is a miracle. So if I’m not going to use this as an opportunity to take the skill sets — some of it, I was born with, some of it, that I’ve crafted, some of it, the communities have helped me craft — and try to leave society a little bit better than the way we found it, I just don’t know why I would get out of bed truly.

A lot of that is not just my beliefs but those of so many people that are before me too. Martin Luther King said you could be a preacher all you want but if you’re not going to move the needle forward, what does it matter? Why are you a man of God? Obviously, paraphrasing. But I believe in that. I just do. I don’t think the individual is ever as important as the community. I think a lot of us have an opportunity to get the community back together a little bit, and the theater and art is that. It literally is a community gathering experience that we’ve gone away from because of our phones or whatever.

It’s been almost an hour already! I have to start asking my final set of questions. What movie are you currently on the set of?

I can’t tell you too much. But I have two movies I am going to be producing. One of which I will be a director of. I also just shot in Egypt the new Guy Ritchie movie. He made the remake of Aladdin, and it stars John Krasinski, Natalie Portman, myself, and Donald Gleason.

Is there a character or role you’ve always wanted to perform that you haven’t gotten an opportunity to play?

I have always wanted to do a romantic comedy.

Yeah? Isn’t that already “You Hurt My Feelings”?

I know, but like a real old fashioned fall-in-love, fall-out-of-love, go-on-an-adventure type movie.

Fair. Why haven’t you done it yet?

I don’t know. Why don’t you make that happen?

Well, we’ll see. Maybe people will see this and be like he said he wants this, we’ll pitch him that.

Done and done [Laughs].

How did the fame from “Succession” impact your life?

Changed it so much. It was just another level that moved the needle forward. Meaning, you know, I was nominated for a Tony in 2011 for a play with Robin Williams and that moved the needle. Then “The Accidental Wolf” moved the needle as a producer, writer, and director. Then the next thing was “Succession.”

Just to tell you how fucked up the world is, prior to succession, 99% of the time my characters had accents from the Middle East. Now since “Succession,” I only play assholes. Rich assholes. But prior to this, I mean, look, “Guards at the Taj,” accent, “Bengal Tiger,” accent, “The Humans,” was an accent. Because they weren’t seeing me.

You have two daughters. Are there ways in which you try to share your values to ensure you pass that down to them? And in light of that, are there ways in which your work and the decisions you make — given your identity as an Iranian and the impact it is making on all kinds of people and not just people of your own identity — conflict?

Always. I’m going to say this very humbly, I hope this doesn’t come off as cocky, I think I could have been rich like 10 years ago if I just played all those terrorist roles. But when I was 25, I didn’t play a terrorist role and guess what happened? I don’t work in film and TV. There was nothing else. And I wasn’t doing victims either; I don’t like us being victims. It just bothers me. It’s cringy.

So, yeah, I think if you’re talking strictly like physically, there would be more money in my pocket right now, which would have changed my children’s lives. But that is not the case. That still happens to this day. You’d be shocked. I got a script the other day of where I’m an alien, but I’m pretending to be a terrorist to find another terrorist from the future. The experience of receiving that is like oh, cool. Because that’s the pocket that we live in.

So yes, it impacts, and I tell them that. Also, all the work that we do here at Waterwell, I try to instill my values. I’m like 99% Iranian. What you’re seeing is an Iranian with an American accent. I try to instill them with those cultural human values that show that people are beautiful.

You were talking about destiny earlier.

Yeah.

At the time, I worked with Robin Williams on Broadway, I was 30, had two kids, was broke, unemployment-check-broke-broke-broke broke. Everybody, my friends, actor friends were like, you can drop Waterwell now, you’re on Broadway. You made it, drop it. And there was really one person that was not doing that. That was Robin. Because, well, why would you drop it now? He was a man of service. I know that word is loaded, and I don’t mean it to be loaded but he was a man that always believed in others before himself.

At the end of the day — and this is an Iranian idea — we’re all gonna die and on that deathbed, I’m not gonna think about how much money I made or did not make. It just doesn’t fucking matter. Nor am I gonna think about why I didn’t play that part. I’m probably just gonna be surrounded by people that love me and the ones that I loved. And if I am thinking about the wrong things, then I don’t think I’ve lived a valued life.

“At the end of the day — and this is an Iranian idea — we’re all gonna die and on that deathbed, I’m not gonna think about how much money I made or did not make. It just doesn’t matter. And if I am thinking about the wrong things, then I don’t think I’ve lived a valued life.”

You graduated from Indiana University after studying Theater, drama, and Persian studies. Shortly after, you moved to New York from Indiana. Do you have any quirky experiences, good or bad, or a story that just speaks of moving to New York that you’d like to share?

On my first day in New York, I drove in with my stuff in maybe a small U-haul I rented. Then I’m like I wanna go to Times Square; I lived in the neighborhood. There was a man who was standing towards Times Square. Pants down. Peeing directly into Times Square. And I was like, ‘Home.’

What a welcome.

But I do remember that day, going to Times Square and also having the fear of, ‘This is not gonna work for me.’ There’s no way I can handle this. It just felt like there were no Iranians in film, TV, and the theater; no Iranian that started a theater company. Nothing. Everything felt crazy, but weirdly it just moved forward.

Another memory was we were so broke and had no money. I would buy a muffin and a coffee for $1 about five blocks away from the place I was temping at. I would take the chocolatiest sugariest muffin; it was like a deal. I would have two bites of the muffin every hour and the coffee, and that was enough to get you through the day [laughs]. Then, I’d come home and there’s a box of spaghetti because my parents would send me spaghetti. No sauce, just spaghetti.

What would you eat with the spaghetti?

Butter, salt, pepper. Probably just salt actually. Those were the early days of Waterwell. Those early days were crazy because we had no idea what we were doing.

“I think a lot of us have an opportunity to get the community back together a little bit, and the theater and art is that. It literally is a community gathering experience that we’ve gone away from because of our phones or whatever.”

Had you guys foreseen the idea for Waterwell before coming to New York?

We were in Indiana, and 9/11 happened. Tom and I were these justice warriors. Rational justice warriors or whatever we thought we were. We really believe — and still do, and part of why we are even talking is because of that — that theater is the actual mechanism to move society forward. Art.

Throughout the years, one of the things I would say is that two things that remain in our history books are the wars that we’ve fought and the art that we make. Literally, there’s nothing else. You can argue that, well the Acropolis is not art. I argue that it is art.

Tom and I met at 18. Moved to New York at 22. So by 19, 20 years old, we were reading Martin Luther King, Gandhi, the Bible, the Quran. We were just seeing what the world was about. 9/11 really just made charge our drive and mission because we were already thinking about Waterwell’s work prior to it.

What exactly about 9/11 — and this might seem like a naive question — gave you guys more energy to really want to do Waterwell?

Immediately after 9/11, what happened was the target was on my back all of a sudden. Was it Iranians? Was it Saudis? Everyone’s back is in that mix. Part of what’s so fucked up about this is that I don’t know any Iranian that would hurt anybody. It’s just not in our culture to do shit like that. I mean, obviously it happens. We’re not very violent people but perception-wise, what I had to deal with, and kind of still do, is that I walk into the room and I believe in revenge, violence. Sometimes I think I walk into a room, I’m already an anti-Semite. The only way for you to understand that about me, or for me to understand anything about Nigeria, is for me to sit with you and be like, tell me some shit. Tell me what’s going on. We can’t all do that. We can’t always know about every single thing. We can’t, as I always say, read every book in the library or watch every movie. In a way, art is a very easy, cheap, simple, doesn’t-need-anything tool to make that [knowledge sharing] happen. Tom and I latched onto that at age 19, 20, and we just never let it go. Then, 9/11 was a war and we knew. They were gonna fight more brown people in the Middle East, hopefully not Iran. Now, we may be back to Iran. How do you fight that? We thought that theater and Waterwell would be our contribution. I just want to be very clear, we were idealistic and big, and we were like we’re going to change the world but we were also rational. We would always say, we’re going to reach for the moon, but if we land in the clouds, we are still flying.

Even if you miss, you’ll land among the stars. To complete the saying.

When you don’t know anything about nonprofits or starting a theater company — I wasn’t an alumni, my parents have no money, Tom’s parents have no money, we’re just poor kids living in the city trying to make art — it’s freeing.

In the first three years, we did perhaps seven shows, just because we didn’t know. Then, someone’s like you need to become a nonprofit and get a lawyer. We became a nonprofit in a year. We found out it was the IRS’ job to help us become a nonprofit and not to deter us. So we turned in our application. They’re like, denied, and here’s a list of reasons you were denied. They just gave us the answers. We plugged it in and months later we were a nonprofit without a lawyer.

It was just kind of idiocy, bravery, not worrying and not fearing failure in a weird way. I think immigrants understand this very well. When we had the opening of “The Ford Hill Project” in October, there were so many people saying, ‘How do you guys do this?’ First of all, it’s a team of amazing people. Secondly, they’re perhaps saying that because oftentimes they feel like, ‘oh I’m gonna fail at this,’ or ‘I can’t do this’ or whatever. When you’re an immigrant and you’ve gone through the trauma already and all the fucking bullshit, what do you mean you can’t put up a play? Do you know what I mean by that? Like, what do you mean no? What are you talking about? What do you mean I can’t start a company? What do you mean? I don’t understand.

We’ve already done the hard part. The hard part is over. That’s a privilege that we have. It really is. I didn’t even do the hard part. My parents did. I was just around the hard part [laughs], navigating the hard part. So Tom and I both had that energy of like, well, what’s gonna happen?

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity.

Do you know who should be in the next Our City? Email earlyarrival@documentedny.com.