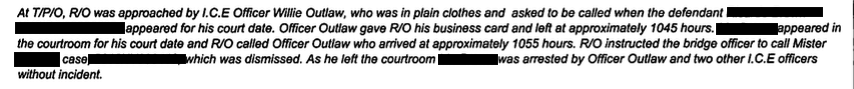

In mid-March of 2017, a court officer at the Manhattan Criminal Court on Centre Street was approached by Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agent, Willie Outlaw. Outlaw, who was in plain clothes, asked the court officer to call him when a man named Stanley* appeared for his court date, then gave the officer his business card. Shortly afterward, Stanley arrived.

The court officer then did something that court administration has previously denied its officers have done: He called Outlaw and told him that Stanley had arrived to the court. Stanley’s criminal case was dismissed, but as he left the courthouse Outlaw and two other ICE officers arrested him.

Outlaw and other ICE agents have been routinely visiting courthouses throughout New York state for the last two years as part of an overall effort to ramp up enforcement actions against immigrants. The goal is to snag immigrants when they arrive for hearings on unrelated matters. While the state Office of Court Administration contends that it does not help facilitate ICE arrests at courthouses, Documented has exclusively obtained reports that detail several occasions in which New York State Court Officers have assisted ICE agents in carrying out arrests.

In response to a Freedom of Information Law request, Documented obtained reports filed by court officers after an arrest by ICE agents. They catalogue 66 arrests by ICE agents in New York State courthouses between February 2017 and August 2018. In six incidents, New York State Court Officers or clerks assisted ICE agents in making their arrests, according to the reports.

The issue of federal immigration officials performing arrests in and around criminal courthouses has united both sides of the criminal justice system, with prosecutors joining public defenders in denouncing what they see as damaging interference with the system’s functioning.

When a defendant is taken into immigration custody before their criminal case is resolved, ICE is under no legal obligation to continue producing them in criminal court, and it often doesn’t, gumming up that case and leaving the defendant in legal limbo. Unresolved charges are then sometimes used by ICE attorneys in immigration court to argue against the release of detainees on bond or parole, further impairing immigrants’ ability to prove their innocence and criminal prosecutors’ efforts to secure a conviction.

“When fear of deportation prevents victims and witnesses from coming forward, or deters defendants from responsibly attending their court dates, we are all less safe,” Danny Frost, a spokesman for Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, wrote in a statement. “While we are not able to comment specifically on the two Manhattan cases—because one has been dismissed and sealed, and the other is open and pending—these Reports make clear why New York lawmakers must immediately pass the Protect Our Courts Act.”

Protect Our Courts Act

The Protect Our Courts Act, a bill introduced by Long Island Democrat Michaelle Solages in the New York Assembly and Manhattan Democrat Brad Hoylman in the State Senate, would outlaw civil arrests without a valid warrant of people attending, headed to or coming from, court proceedings in state courthouses. It would also bar ICE agents from entering courthouses at all, and would grant the state attorney general the authority to sue parties who violate those provisions.

“The willing sharing of information between ICE officials and court staff in the absence of a judicial warrant is alarming,” said Hoylman in an emailed statement. “Our justice system depends on the participation of everyone in our community, regardless of their immigration status.”

“This confirms our worst fears and is deeply troubling,” said New York City Councilman Carlos Menchaca, who serves as chair of the Council’s Oversight Committee on Immigration, in response to the reports. “For these court officers to deliberately aid ICE in identifying, tracking, and arresting their targets is to make a mockery of the court’s integrity as a space that protects due process.” Solages echoed Menchaca’s comments, stating in an email: “Federal immigration agents coursing and arresting immigrants in our courthouses deters individuals from interacting with the judicial system, which in turn endangers the safety of entire communities.”

New York Chief Judge Janet DiFiore, who runs the state’s court system, has so far refused to bar ICE agents from entering and conducting arrests in courthouses, saying that they are public buildings and she lacks authority to do so.

Facing pressure from defense lawyers, district attorneys, and elected officials, the Office of Court Administration (OCA) issued an updated protocol “governing activities in courthouses by law enforcement agencies” in April of 2017. The policies specify that law enforcement officials must identify themselves and their purpose upon entering a courthouse, that the judge be informed if a participant in a case before them is the target, and that “[Unified Court System] uniformed personnel remain responsible for ensuring public safety and decorum in the courthouse at all times.”

The protocol does not specify to what extent court personnel can or should assist federal law enforcement authorities, including ICE agents, but the stipulation about ensuring public safety has been interpreted by some court officers as requiring them to facilitate ICE arrests. OCA spokesman Lucian Chalfen told the Village Voice in November 2017 that “we do not facilitate or impede ICE when they effect an arrest… We ensure that their activity does not cause disruption or compromise public safety in the courthouse.”

Reports show ICE cooperation

The reports obtained by Documented show court officers have helped facilitate arrests. The reports are descriptions of each arrest filed by the court officers on duty, they do not contain details on why immigrants were in court that day or why they were wanted by ICE. Documented was able to confirm the details on certain cases.

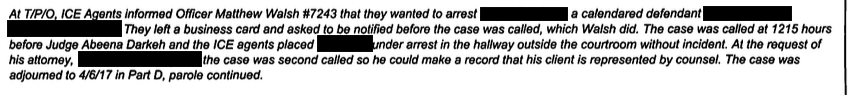

A month before Stanley’s arrest, ICE agents approached court officer Matthew Walsh to notify him that they wanted to arrest Floyel Stapleton, who was due in court for a routine hearing in his misdemeanor assault case. Once again, ICE agents left a business card and asked to be notified before the case was called. Like his colleague, Walsh obliged and called ICE.

Stapleton was arrested by ICE agents in the hallway of the Manhattan Criminal Court as he left the courtroom. According to The Daily News, Stapleton was then detained at Hudson County Correctional Facility in New Jersey, which holds immigrant detainees for ICE.

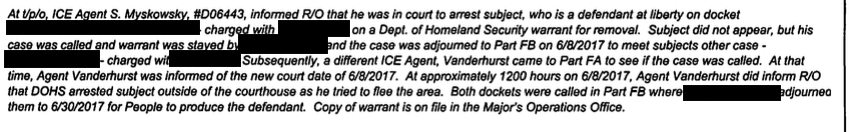

On another occasion, ICE agents appeared in court to arrest Raphael* who had a scheduled court appearance but did not show up. According to the reports, court officers then notified ICE agents of his next court date two days later, at which time the agents came back to the court and arrested him.

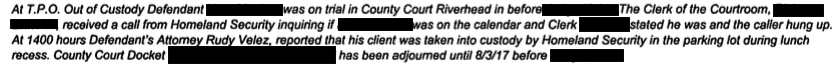

In August 2017, according to the reports, a courtroom clerk in the Suffolk County courthouse received a call from “Homeland Security” inquiring whether Maximo Vera, who was on trial for alleged rape and sexual abuse charges, was due in court that day. The clerk told the agent that Vera was, and 30 minutes later, Vera was arrested in the courthouse parking lot during a lunch recess, according to his attorney, Rudy Velez. Vera was later convicted on the rape and sexual abuse charges. Calendar information is public so it is unclear why ICE agents needed to call the clerk in advance.

“I think it’s outrageous,” said Velez, on his client’s ICE arrest. Vera was originally out on bail, but once arrested by ICE he was incarcerated and appeared in court for the remainder of his trial flanked by court officers. Velez said he believes the treatment could have prejudiced the jury deliberating on the assault and rape charges. He felt the judge in the case should have intervened and not allowed it, but his appeals were denied.

ICE arrests can be prejudicial

“When you have a defendant on trial you’re risking his right to a fair and impartial verdict,” Velez told Documented. “That’s obviously prejudicial. They don’t know the details of [his arrest]. That’s not something that’s explained to them, all they see is that all of a sudden now he’s surrounded by court officers and he must’ve been incarcerated due to something that happened. It obviously has a chilling effect on the jury trial.”

Reached for comment on the details contained in the reports, OCA’S Chalfen wrote that “of the four incidents that you reference, two occurred just as we began to track ICE interactions in our courts and before we issued a new policy, in April 2017, specifically brought about by ICE appearances at court buildings. The latter two were simple requests for publicly available information, contained on eCourts, regarding a future court date and whether an individual was on trial.” He did not address further questions about exactly how officers’ are permitted to cooperate with ICE, or if it was OCA policy to proactively provide information to ICE, public availability notwithstanding.

Dennis Quirk, the president of the New York Supreme Court Officers Association, said that while incidents described are rare, he did not view them as improper. “We have to preserve safety. By cooperating with ICE, and working with ICE, we’re able to accomplish that, so nobody gets hurt. When they start pouncing on [targets] in the hallway, that’s worse. It’s much better when people are taken discreetly.” He likened the interventions to similar ones that occur on behalf of other law enforcement officers. “It’s not unusual for NYPD to call the courthouse and say they’re looking for John Jones on a warrant or an investigation. That happens all the time, but I’ve never heard of it happening with ICE.”

After calling some supervisory officers, Quirk called Documented back and added that he had been told that in each of the incidents involving court officers, ICE had presented a warrant. Asked if these were regular judicial warrants or ICE administrative warrants—which ICE can issue itself, without the need for a judge to sign off, and which are not generally considered legally binding—Quirk said he didn’t know. “We’re not lawyers that determine what kind of a warrant somebody has, if they have a piece of paper that says it’s a warrant, a warrant for somebody, that’s it.”

Two of the reports detail court officers physically assisting ICE agents in carrying out an arrest. A separate 2018 incident, not detailed in the reports, was caught on camera and showed court officers assisting plainclothes officers in arrests.

Press officers at ICE were furloughed due to the federal government shutdown and were not yet available for comment.

*The names of some individuals have been changed to protect their identity.