This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletter, or follow The Marshall Project on Facebook or Twitter.

She was undocumented for over ten years since arriving in the U.S. from Guatemala with her mother. After gang members killed her father in their home country, she petitioned New York’s juvenile court to declare her “abandoned” by her father. That ruling would allow the then-15-year-old girl to apply for a Special Juvenile Status with a pathway to permanent legal residence.

With the court’s ruling, she got approval from a federal immigration agency to request a green card that would allow her to live and work in the U.S., but almost four years later, she’s still waiting for the card to come.

“I was able to go to school, but I couldn’t work,” said the girl, whose name we are withholding due to her vulnerable situation. “I couldn’t do all the things others kids can do, like get jobs and study abroad.” Because she doesn’t have a green card, she does not qualify to work legally or to receive federal public assistance.

Her mother—who is undocumented—was paying for college. But her mother’s work hours were cut due to COVID-19. Unable to pay the tuition and falling behind on rent, the teenager had to drop out of college and start working to help support her family. Her mother said they now owe their landlord $14,000.

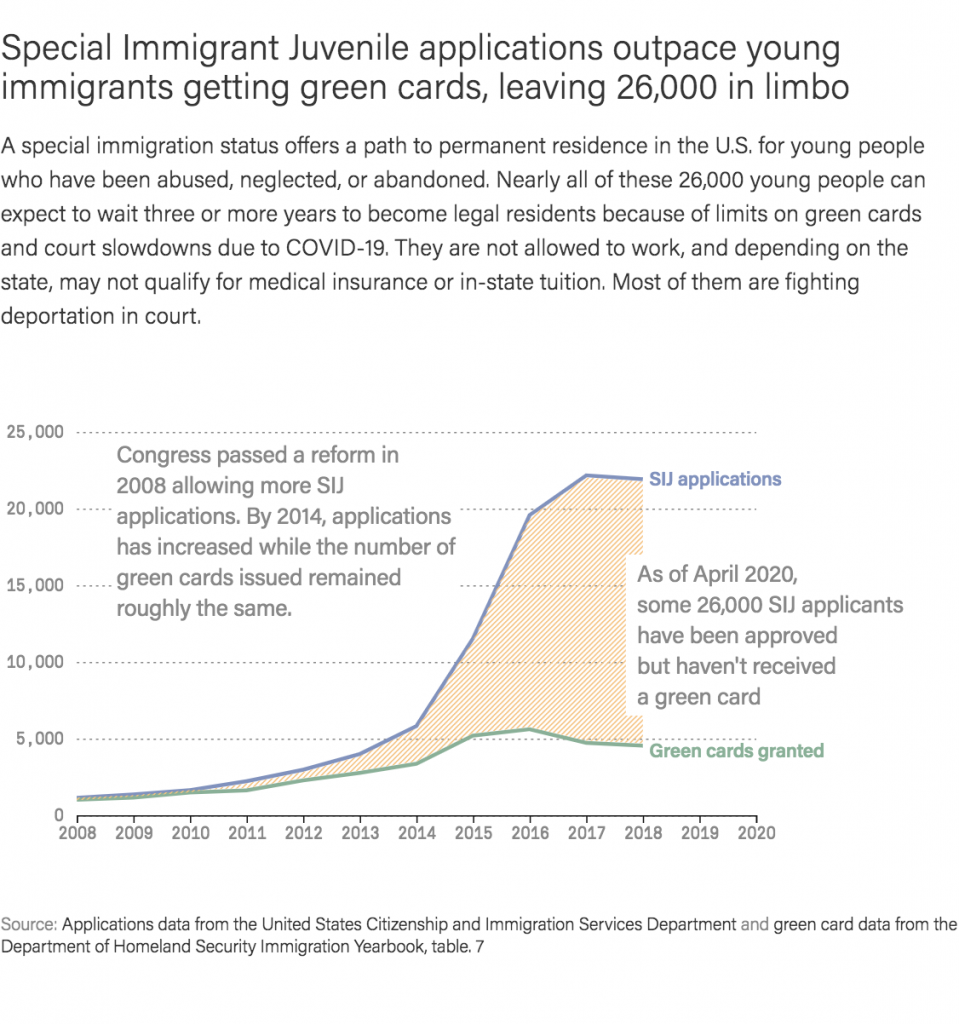

Some 26,000 young people like this teen are stuck in limbo and vulnerable to deportation, a Marshall Project analysis shows. Nearly all of these young people can expect to wait three or more years to become legal residents because of limits on green cards and court slowdowns due to COVID-19. They are not allowed to work, and depending on the state, may not qualify for medical insurance or in-state tuition. Most of them are fighting deportation in court.

Critics of the juvenile immigrant program argue that it is exploited by families in search of economic opportunities and gangs planning to conduct criminal activity in the U.S. The Trump Administration tried to halt the program altogether, claiming it was riddled with loopholes.

The young people we spoke with described a different reality. They said their lives were on hold and that they felt forced to make tough choices that could jeopardize their cases. Many of them fled their home countries to escape gang violence or parents who abused them.

“I am always afraid. I have to walk extremely straight and not to do anything that will hurt my case,” said a teenager from El Salvador who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “But I don’t have a choice. I have to work. And I know it’s going to be three very long years until I get my green card.”

Also read: Essential Subway Workers Allege Underpayment and Dangerous Conditions

—

Special Immigrant Juvenile status was created by Congress in 1990 to provide “humanitarian protection for abused, neglected, or abandoned child immigrants.”

After arriving in the U.S., young people must go to state juvenile court to request a ruling of abuse, neglect or abandonment by one or both of their parents. They must also be placed in the custody of a legal guardian or in foster care. If the state court approves the request, they can then apply to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), the federal agency that manages the nation’s legal immigration system, for the juvenile status.

Although an approval gives young people permission to request a green card, paradoxically, it does not grant them authorization to remain in the country. So most of them must simultaneously fight deportation in immigration court until a green card becomes available.

And green cards are hard to come by.

Caps limit green cards by type of application and by the country of origin. Young migrants from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador are the most affected by the caps. They have far exceeded their country’s green card limits and the lines have gotten so long that USCIS is only processing applications submitted before May 2017.

There are at most 9,940 green cards available to program applicants every year. On average about half of them go to these young migrants. As of Oct. 1, 2019 the USCIS had approved more applications for the special status in the previous year than in the program’s 30-year history, adding to the backlog. Now about 26,000 young people at risk of deportation can expect to wait three years or more to get a green card.

“The Department of Homeland Security has already said that these vulnerable and victimized children should be permitted to stay, yet the same agency insists that they should be removed from the United States,” said Beth Krause, supervising attorney at the Legal Aid Society. “It’s illogical. It’s a waste of time and money. It backs things up.”

—

Lawyers in multiple states told us that some judges are unfamiliar with the special status for victimized youngsters, especially in rural counties. In one Georgia case, a juvenile court judge requested that a lawyer bring a letter from the USCIS stating that the judge was allowed to make a ruling. In the time that it took the USCIS to write the letter, the young person aged out of eligibility.

“There are places where judges don’t see any of these cases so it’s new to them and they don’t realize they can issue these rulings,” said Noah Montague, an immigration specialist in Nevada. “There is simply a lack of uniformity from state to state and even county to county.”

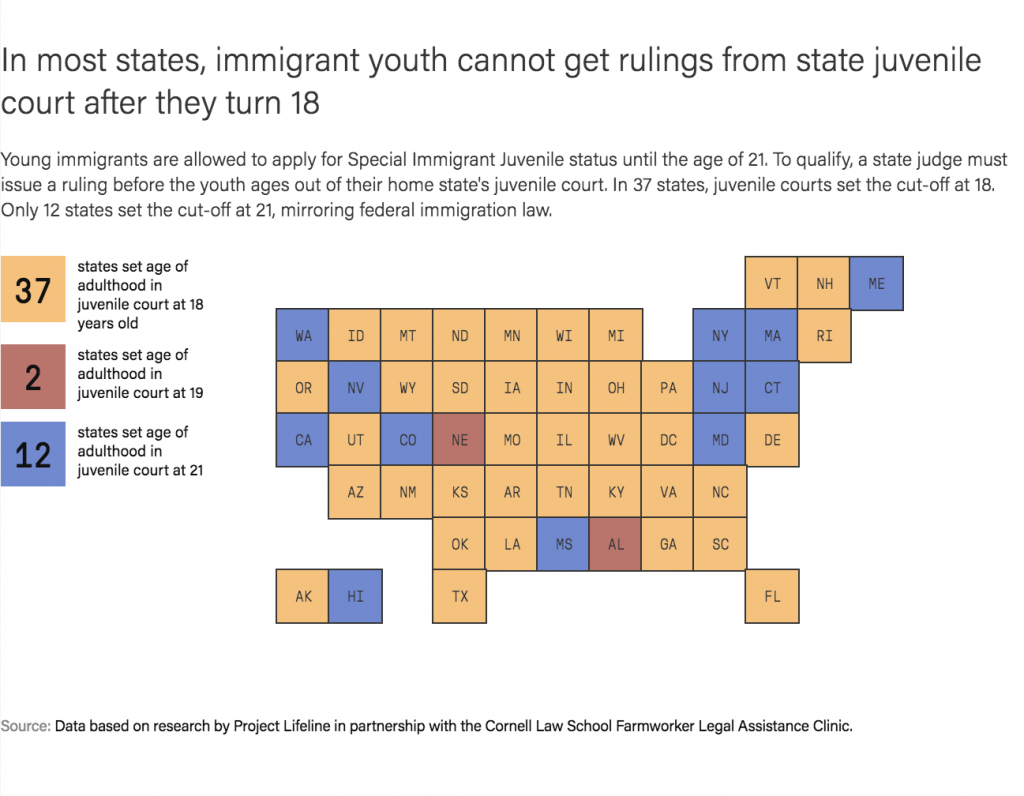

The federal government considers people who are 21 years or older to be adults, but some states put it at 18 years old. That has led to some applicants “aging out” of the state juvenile court system even though they still qualify for the status under federal rules.

In New York, the state court system created an advisory council to address immigration issues that arise in family court. According to their homepage, the council sets family court standards and provides judges with up-to-date information about immigration law.

“The typical response from family court judges unfamiliar with immigration law was that we were just trying to find a loophole to get immigration status when everyone else is waiting on line patiently,” said Theodore Leibman, who sits on the Advisory Council on Immigration Issues for the Family Court of New York State. “But with the advisory council that has all changed.”

Also read: Why I Led a Hunger Strike Against ICE in New Jersey

—

Adding to the frustration, immigration courts have been forced to close by COVID-19 and thousands of young people are seeing their deportation cases drag on even after becoming eligible to get a green card.

“COVID-19 compounds the anxiety of living with the fear of deportation,” said Rachel Davidson, lead attorney at The Door in New York City, a nonprofit providing youth and legal services. “These are vulnerable kids and because the courts are reshuffling their schedules, they remain unprotected.”

For the majority of the pandemic, many immigration courts remained open only to immigrants confined in detention centers. For immigrants who aren’t held in detention centers, like SIJ applicants, courts will not fully reopen until Feb. 19, according to the immigration courts’ website. The reopening date has been repeatedly pushed back since the pandemic started.

Immigration judges have the authority to terminate these deportation cases without requiring the young person to attend a hearing. To do so, the Immigration and Customs Enforcement prosecutor and the judge must agree to close the case pending the green card approval.

Court documents show that up until November of last year, judges and ICE prosecutors were declining to close these cases, citing decisions from former Attorney-General Jeff Sessions and President Trump’s enforcement priorities. Lawyers from the Legal Aid Society said that requests are now being approved more often. But that still leaves thousands of young immigrants who are eligible for green cards at risk of deportation.

On the first day, Biden unveiled a comprehensive immigration reform bill that includes provisions to eliminate the per-country caps that contributed to the backlog of special immigrant juveniles, and speed up green card applications. But the bill’s prospects of passing a polarized Congress are highly uncertain, and it’s unclear whether the proposed changes would benefit these young immigrants.

In a request for comment, a USCIS spokesperson said that although the agency coordinates with the Department of State to determine how many green cards it can approve per year, the number of green cards available is set by federal statute, adding that “questions related to efforts to increase visa availability to reduce priority dates should be directed to Congress or the White House.”

Also read: DOJ Appeals Ruling Limiting Immigrant Detentions Without a Court Hearing

—

In early 2018, the Department of Homeland Security issued a statement pledging to the “end abuse of Special Immigrant Juvenile status,” claiming it was exploited by minors, migrant families and human smugglers.

In an unannounced policy change the same year, the Trump Administration tightened the age requirement on these special visas, issuing denials for applicants over 18, and reopening completed cases to retroactively deny them. Hundreds of cases were denied and at least five young people were deported before the policy was overturned by a federal court order.

But there is little evidence that the program is beset by “rampant fraud,” as some Republicans have suggested. The Center for Immigration Studies, a think tank that advocates for tighter restrictions on immigration with close ties to the former administration, was unable to cite evidence to support the claim of widespread fraud beyond a 2015 NBC News investigation in New York alleging that hundreds of young men arriving from the same region of India told “similar stories” at the Queens Family Court in pursuit of the status.

Some lawyers working on these cases said that young people are sometimes approved who do not precisely fit the criteria. Some of the young immigrants interviewed also said they came to the U.S. because their families could not protect them from violence and poverty at home.

That said, the status is the only immigration benefit that requires both judicial review from a state court and scrutiny from a federal immigration agency. Critics and proponents alike acknowledge that it is an intensive application process. Both state juvenile courts and USCIS have the power to deny these cases, yet the majority of them—about 90 percent in a typical year—get approved.

Support our immigration reporting by becoming a member

—

These young people stuck in green-card limbo described constantly watching their backs, trying to avoid the police and missing out on some of the best parts of being a teenager. Some wondered if it might be simpler to stay undocumented.

“We are more visible than someone who is undocumented,” said a young immigrant we spoke to on condition on anonymity. “Maybe it would be easier if they didn’t know that we were here.”

Correction: A previous version of the story stated that a young immigrant who received Special Immigrant Juvenile Status could lose their status and potentially face deportation if they are caught working illegally. Although they are not allowed to work, an SIJ applicant will not lose their status if they are caught working. They could still be caught in an ICE raid, put into immigrant detention, or deported.