Haitian multimedia journalist Ralph Thomassaint Joseph joined Documented last spring with a clear mission to make news: “My job as a Caribbean Communities Correspondent is a kind of liaison officer,” he told me when I interviewed him last spring. “I will create a two-way conversation between Documented and the Caribbean communities of New York. It’s a strategy to make the media closer to its audience, grow interaction, and continue with what Documented has been doing. It’s a media to inform but it’s a media of service too.”

Over the past year, Ralph has been digging into Caribbean communities in New York. We spoke about why 66% of the respondents said public benefits programs are the main topics they are interested in when consuming immigration news; why more than 70% of respondents use the apps Nextdoor or Citizen to know about their neighborhoods; why there is a need for more research about Caribbean nationalities in the U.S.; the opportunities for potential media products, and more.

Fisayo Okare: How does this research about the Caribbean communities in New York compare to your previous work experience with the Haitian news source AyiboPost?

Ralph Thomassaint Joseph: Audience survey in media is something I discovered, frankly, during my master’s degree in digital media at NYU. Although I was leading a competitive digital news media in Haiti, it was the first time I saw how important audience research was for the media. This experience at Documented is my first time immersing myself into a specific group — immigrants from the non-Spanish speaking Caribbean region— to understand their news needs.

What surprised you the most during this research?

At Documented, we started with a certain idea of the Caribbean, assuming that since Caribbeans have similar cultural traits, they would form a unique community in New York. The research proves that we were wrong. There are many Caribbean communities in New York and people from the Caribbean understand their community mostly as their immediate neighborhood, and many times, as the specific country they come from.

Also, I was surprised to discover that there was very little research already done about the Caribbean communities in the U.S. and in New York specifically. I discovered that it wasn’t until the 2020 U.S. census that Caribbean nationals could identify themselves based on their nationalities.

What was the most difficult part of the research process for you?

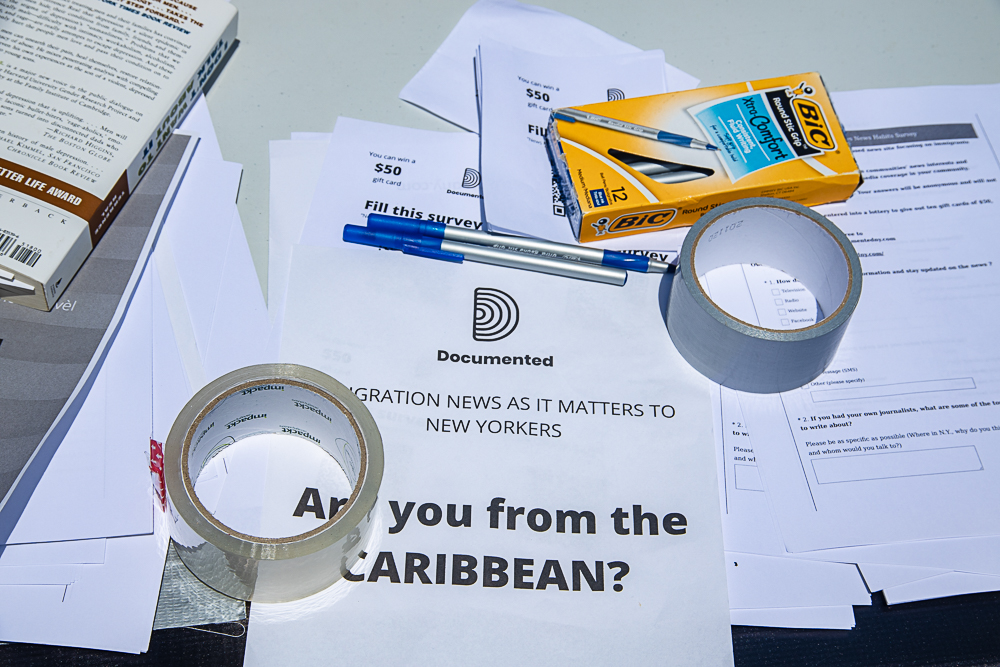

When I was designing the questionnaire, and testing it with experts and organization leaders, it was pretty easy because they were quite accessible. The most challenging part was implementing the research on the ground and finding different Caribbean nationalities in New York.

Though there are a few exceptions, it is pretty hard to find Caribbeans gathered in organizations as ‘Caribbeans’. There are organizations under the Caribbean umbrella category, but they serve all kinds of clients in New York, not just people from the Caribbean. It was easier for me to get access to Haitians because many organizations in New York are assisting newly arrived Haitian asylum seekers.

I did find more potential respondents too but they were not interested in participating in the survey. This has an impact on the sample size.

It was not easy to identify ‘who’ the Caribbeans are because they’re mostly Black and live in Black neighborhoods where they are mixed with African-Americans, Black Africans, and Black people from other countries. It was also challenging to find Caribbeans in low-wage jobs because most of the time they are doing many shifts, working long hours, and living in remote places.

66% of the respondents said public benefits programs are the main topics they are interested in when consuming immigration news. What’s the reason behind this?

Once immigrants land in the U.S., they usually first look for resources: food, schools, education and professional apprenticeship programs, and public healthcare — because they cannot afford to pay for healthcare. Once it’s public, it’s free or cheaper for them to access as they begin their lives afresh. Many Caribbean immigrants left their countries for a better life in the U.S., for these people; public benefit programs come at the top of their interests.

29% of respondents said that they would improve the current media coverage by adding more “positive news”. What does “positive news” mean, and why do you think this is lacking in the media?

During the two phases of the research, immigrants constantly said that most of the time the media comes to Caribbean communities, reporters expect to report about crime, drugs, violence, or something bad. But the Caribbeans say that “our lives are not just about crime, violence.” There are so many Caribbeans who are nurses, cops, cleaning people’s homes, taking care of children, doing business in New York, contributing to and building wealth in the United States, paying taxes and contributing to improve life. Caribbeans are also very proud of their culture, so they would like to see this represented more in the media since the type of coverage they denounce projects a bad idea, reinforcing the kind of vision people generally have about Black people in the United States.

More than 70% of respondents use the apps Nextdoor or Citizen to know about their neighborhoods. What does your research indicate about the reason for this?

The main reason is to know what’s going on in their neighborhood. Citizen is an app about safety, it’s used to report crimes, happenings in neighborhoods, etc. So people are interested to know what’s going on around them. Nextdoor is the kind of app to know who your neighbor is, and how you can get access to services in the neighborhood.

What opportunities did your research reveal about potential media products?

Many consumer news platforms with Caribbean communities include groups on Facebook, and WhatsApp. Some Caribbean immigrants also read newspapers and watch TV. One of the things that was new to us at Documented was discovering that respondents were using apps like Nextdoor and Citizen. We think experimenting with pushing content on an app like Citizen is not possible because of the way the app is designed. But on Nextdoor, since it’s about hyperlocal communities, we think that it’s worth trying to experience news content, getting neighborhood feedback,, and reaching out to these little pockets of people living in their different Caribbean neighborhoods in New York.

Also Read: Caribbean and Chinese Communities Audience Research

Also Read: 5 Reasons Why We Researched Caribbean and Chinese Immigrant Communities

Also Read: The Methods We Used to Research 1k+ Immigrants in NYC