A class where children learn to make chocolate while building a sense of community; a poetry workshop where migrants write and recite their stories of migration; and a wellness event where immigrant women youth explore different self-care stations like massage, affirmations and nail painting. These are some of the workshops implemented by local Brooklyn nonprofits Mixteca, RaisingHealth, and Brave House, which have introduced culturally tailored workshops to raise awareness about mental health within immigrant communities.

These organizations say that these workshops have helped combat the stigma surrounding mental health while addressing the lack of resources in communities where accessing mental health services is challenging. Data collected by these organizations show that demand for the programs has increased with the arrival of more than 200,000 migrants in NYC since the spring of 2022, further emphasizing the need for culturally sensitive services to raise awareness about mental health.

A report released by the World Health Organization last year outlining the main factors impacting the mental health of refugees and migrants found that mental health access is not prioritized in these communities due to lack of affordability, language barriers, stigma and concerns around confidentiality. The report is part of the Global Evidence Review on Health and Migration (GEHM) series, which uses an evidence-informed tool for policy-makers on migration-related public health priorities of the Department of Health and Migration.

Claudia Aranda, mental health and psychosocial support manager at HIAS, a nonprofit serving refugees and asylum seekers globally, said that the impact of migration on mental health is compounded by the migrants’ experiences of violence in their country of origin or during their migration journey.

Also Read: The Unspoken Toll Migration Has on Mental Health

“There are people who have experienced so many situations that lead to a lot of distrust and who prefer not to talk about it [mental health] out of fear, mainly because this fear comes from that distrust,” Aranda told Documented in Spanish.

She added that during the journey, migrants don’t have the time to address their mental health because “their journey is still very long, the risk of breaking down at this moment is very high. They fear they won’t be able to continue on their path.”

Different ways to heal

Lorena Kourousias, executive director of Mixteca, a nonprofit helping migrant communities in Sunset Park for decades, has seen firsthand the challenges that prevent migrants from accessing mental health services. At Mixteca, she said, many come asking for legal assistance, help enrolling in health insurance, IDNYC, and Fair Fares MetroCards while also requesting food, clothes, and diapers. The last thing on their mind is their mental health, she told Documented.

In 2023, Mixteca released a survey highlighting the need for mental health services in the immigrant community, which has been compounded by the population’s immediate needs for food, clothing and shelter. Mixteca’s mental health and wellness workshops have seen an increase in attendance in the past two years, Kourousias said, since the arrival of more than 200,000 asylum seekers to New York City. She said that Mixteca now has four full-time social workers, as opposed to one social worker part time in the past.

“Adapting to a new culture, a new language, new society, new norms — it can be really overwhelming and isolating for the community,” Kourousias said, adding that connecting people with practices they are familiar with has resulted in increased engagement.

“Our community has different ways to heal, because our community doesn’t heal exactly or only by sitting down and talking about the trauma or talking about what happened to them but also when they are in community, sharing something they are proud of and something relatable.”

To understand the isolation faced by migrants, Documented reached out to our WhatsApp community to open a dialogue about mental health. One of our readers, who is a construction worker from Corona, Queens, said that, “Solitude is a bad partner for an immigrant, but it is the only partner that one has when someone migrates looking to prosper. It becomes like an addiction.”

Mixteca sees the value in building community to improve mental health outcomes. A typical wellness event hosted by Mixteca may include a curandero, a spiritual healer, yoga, and a Tai Chi instructor. Including these diverse exercises are intentional, Kourousias said, adding that their approach is “to offer opportunities to heal everyone in their own way,” rather than directly introducing the topic of mental health to the community, which often faces stigmatization. As Kourousias also recognizes the value of a more traditional approach, Mixteca has hosted group therapy sessions where more than 30 people attend, she said.

Language is key to wellness

Similarly, the Brave House, a nonprofit in Brooklyn supporting immigrant women and gender-expansive youth in NYC, has also had success in making mental health more approachable in the communities they serve.

Mabel Smith, director of development and operations at the Brave House, said that during a recent event, called “Wellness Wonderland,” their community members were given the opportunity to experience different self-care stations like massages, affirmations, and nail painting, among others — all of which are assisted by team members who are bilingual in English and Spanish. “It is important first and foremost that services are offered not only in a setting that is warm and friendly but also in a language that is accessible for members,” Smith said.

Smith added that one of the members, Maria, who attended the event, told her that she had never heard of or was not even aware of what they could do with self-care and that it has made a difference on her life.

But beyond language access, “we feel strongly that the Brave House should always feel like a safe, radically hospitable place for folks of all backgrounds and statuses of immigration,” Lauren Blodgett, founder and executive director of the Brave House, said.

Blodgett, who is an immigration attorney, told Documented that the issues affecting mental health are intertwined with the obstacles faced by migrants navigating the immigration system.

“Our staff therapist strengthens our holistic approach by working closely with our legal team to bolster our clients’ claims for humanitarian protection based on the violence of their past and the trauma that persists today,” Blodgett said, adding that they work with their clients before a hearing to review anxiety-relief strategies to assist with their performance.

Along with support from Applied Wonder, a company which combines peer-reviewed science, technology and art to create products that help reduce anxiety, the Brave House created the Healing Room—a multisensory, nature-inspired space designed to regulate emotions.

Also Read: NYC Relief Organizations Thrive on Volunteers and Donations to Help Newly Arrived Migrants

Psychoeducation and migration

The World Health Organization has documented that refugees and migrants face different risks and needs for support when it comes to mental health, but there is still much to learn about this population. The WHO report “Mental Health of Refugees and Migrants: Risk and Protective Factors and Access to Care” states that the organization has limited data on how migration impacts the lives of other groups: older migrants, LGBTQI+, and internal labor migrants and affirms the need for more detailed, long-term research.

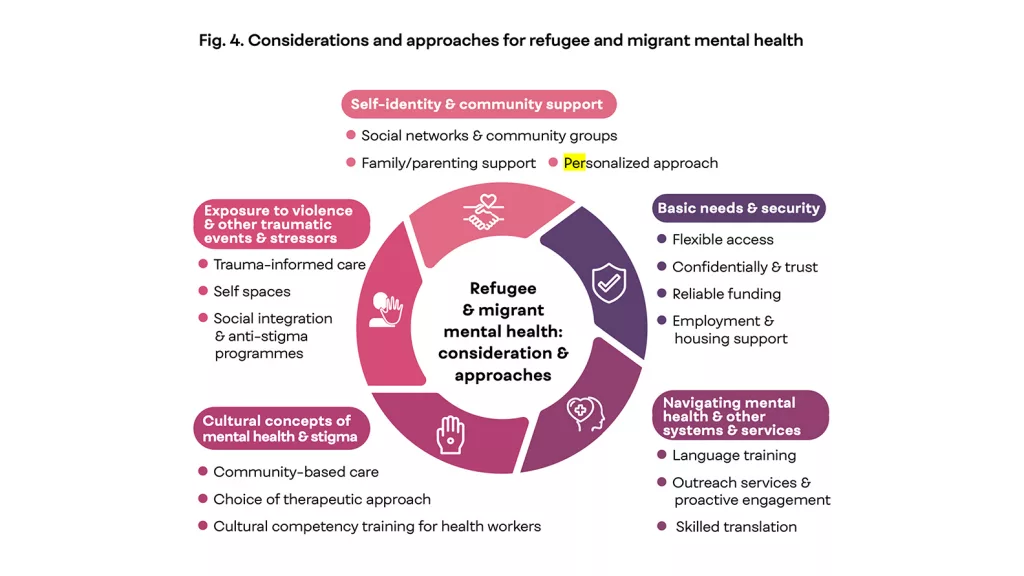

The report did find evidence that considering identity and community support, basic needs and security, cultural views on mental health and stigma, language needs, and clients’ exposure to trauma can improve mental health outcomes for migrants and refugees. All of these principles can be found in the approaches to wellness and mental health practiced by Mixteca, the Brave House, and Raising Health.

The efforts of the organizations are measured by participant feedback, along with a combination of data-informed surveys to track their efficacy. Aaronson explained that Raising Health uses the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) and GAD-7 (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7) assessments, which are standardized self-administered tools used to screen for the severity of depression and anxiety symptoms, to see if the clients have seen improvement. “We look at those results over time, over the course of someone’s therapy plan, basically, to see how their improvement has been,” she said.

The Brave House uses a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection, as well as ongoing feedback conversations. “We track attendance, engagement, and growth. We have one-on-one conversations with members to gather feedback on the program’s overall effectiveness, content, and members’ individual ideas for the future,” Smith said, adding that aside from survey data collection, the therapists also evaluate the members’ mental health progress using clinical scales. “[They] are re-evaluated in 3- and 6-month periods.”

Kourousias added that while the Mixteca workshops have been well received and have seen an increase in attendance, it is hard to pinpoint a measure of success because a person’s mental well-being could improve due to a combination of efforts provided by the organization, social workers, healers, and the supportive space.

She added that additional barriers to data collection, such as funding, staff shortages, and the reluctance of people to participate in surveys due to time constraints, could prevent organizations from gathering more data. “Sometimes we do not have the time to track, to be honest. We are growing and now have four full-time social workers, but there are still not enough people to support these efforts,” Kourousias said.

Eliminating barriers to accessing mental health

One of the challenges that migrants, particularly those with irregular status or who have recently arrived, face is the lack of health insurance. The average cost for a mental health session without health insurance ranges anywhere from $100 to $200 in the United States. “It’s much harder to receive mental health care without insurance or especially for lower-income people,” Grace Aaronson, capacity-building coordinator at Raising Health, said.

To combat the barriers to entering mental health services, Aaronson said that they have hosted no-cost workshops to spread the word about mental health while helping to destigmatize it. One example is a workshop that helps recently arrived migrants write and draw while practicing stress management techniques, like breathing exercises, working with plants, and other creative ways to release stress. “All while we are having conversations with the community throughout the workshop,” she said.

The psychoeducational workshops have served more than 700 people in the last year alone, and is overseen by Lysna Paul, Manager of Community Health.

Aaronson highlighted that the vocabulary used during the workshop is also important. “They might not have a certain vocabulary around mental health that is used by clinicians, so there are just different approaches we have taken with that audience in mind,” she said.

Hewett Chiu, president and CEO of Raising Health, said that the approaches at the organization take into consideration the experiences that migrants might have had during their journey to the United States. He illustrated that having a security guard, which is often included in traditional settings, at the front entrance could trigger people due to their experiences with law enforcement. “So we don’t have sort of like security people standing outside our facilities,” Chiu said.

He also added that asking people for health insurance and identification are systemic artifacts that could deter people from accessing the services. “We do not ask people for identification,” he added.

Chiu reiterated that while tailoring the workshops to their clients’ cultures is essential to serve the Spanish and Chinese communities in Sunset Park, the importance of traditional and clinical therapy is just as crucial. “They should complement one another,” he said, adding that people who attend the workshops can choose to be connected with a therapist to pursue one-on-one sessions.

Also read: Donations and Volunteers Needed to Help Migrants in NYC