It’s a Monday afternoon and Karen Salgado’s children can be heard playing in the background while she speaks on the phone. Like many of New York City’s youth, they have had to find time to unwind in the same Jamaica, Queens apartment where they hit the books.

“They like to jump up and down on the bed,” says Salgado, 44, with a jovial giggle. But for the Honduran-born household cleaner, that joyfulness has been harder to come by in the last few months.

Unemployed since the first week of April, she has fallen behind on her rent and owes her landlord about $1,000.

“It’s been very bad here. We need money so that we can move forward and pay rent, light and gas,” she says.

Salgado is among many immigrants who have been negatively affected by the pandemic. Latinx New Yorkers account for 33.4 percent of COVID-19 deaths, while accounting for 29 percent of the city’s population, and have suffered job losses at higher numbers. The stark inequalities that plague New York were laid bare as crowded homes, food insecurity, lack of access to healthcare and public assistance, and working in bludgeoned job sectors have made it more difficult for Latinx New Yorkers to weather the crisis. They have largely needed to depend on themselves and community-based organizations.

Food Insecurity and Cramped Apartments

It was mid-March and MASA, a community-based organization in the South Bronx working with the area’s Latinx population, particularly those of Mexican descent, was holding a community meeting about the nearby school where many members’ children attended possibly shutting down. Though Aracelis Lucero, the organization’s executive director, knew at that point that a shutdown was inevitable, she did not expect the announcement to swiftly arrive the following day.

Becoming increasingly fearful, some parents had already ceased sending their children to school and the apprehension continued to grow.

After the shutdown, the first round of calls from worried members, nearly all of whom are Latinx immigrants, began to hit MASA’s phones.

“That’s when it really hit us,” says Lucero, who notes that food insecurity was members’ top concern, many of whom live paycheck to paycheck and struggled to break the news to their children that their food supply was waning. “Some parents were taping the fridge.”

Citizens and green card holders can apply for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), sometimes referred to as food stamps, to help defray the cost of groceries. However, undocumented immigrants and other residents with non-permanent status don’t qualify for SNAP and other forms of public assistance and benefits like unemployment insurance and Medicaid, narrowing their support options in this period of crisis brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Because her children were born in the United States and have permanent status, Salgado qualifies to receive SNAP.

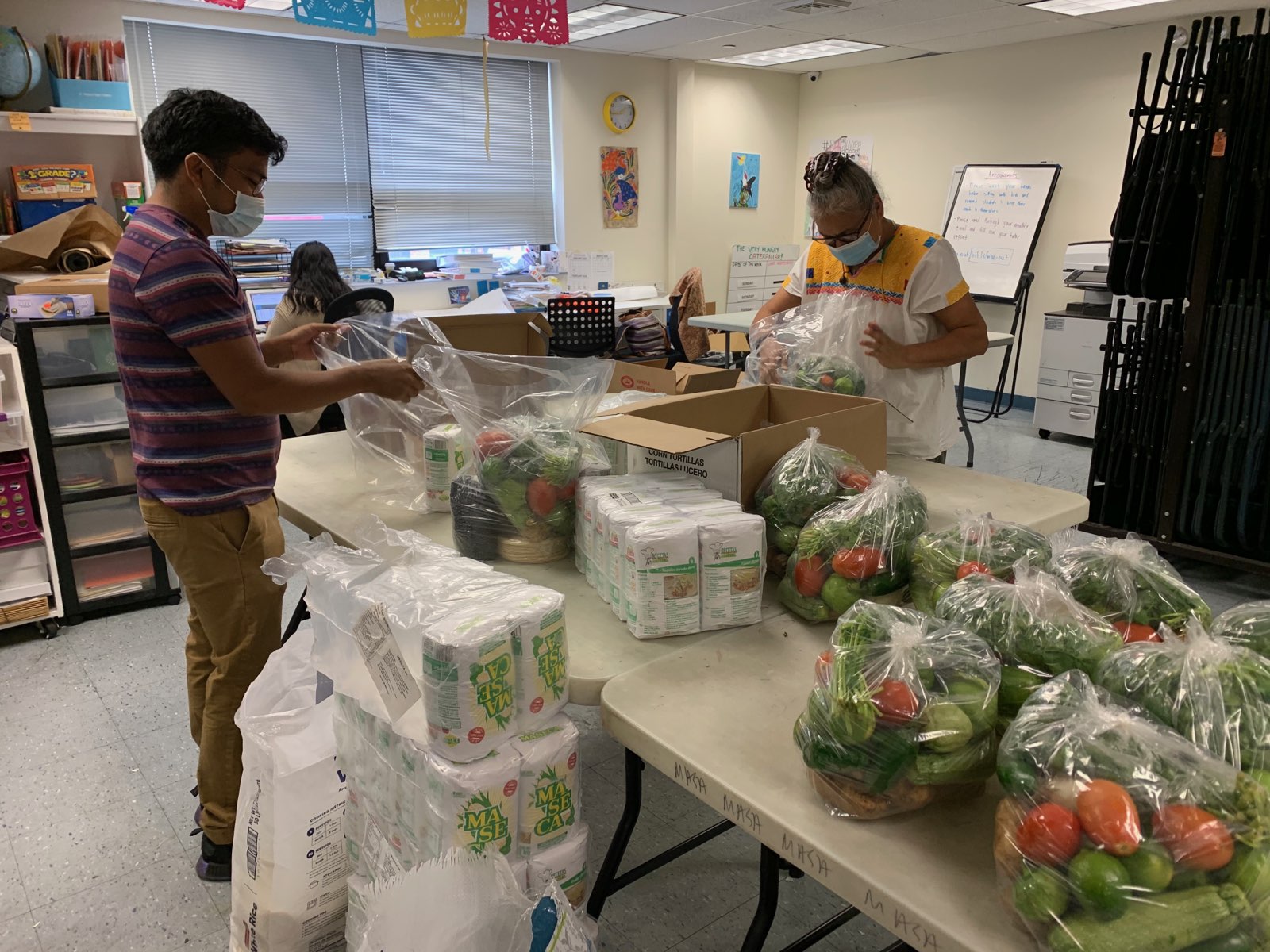

MASA has worked to feed over 300 families per week through its food support program that provides fresh produce, hot meal deliveries, and staples like maseca which can be used for traditional Mexican dishes.

To help buttress the estimated 60 percent of foreign-born constituents and the 40 percent that have non-permanent status, Assemblywoman Catalina Cruz has run a food pantry six days a week that also doles out supplies for infant care like diapers and baby formula. The majority of the concerns of the people she represents are food insecurity, lack of health care, and unemployment, the elected official noted, whose district encompasses Elmhurst, Jackson Heights, and Corona, three of the most devastated neighborhoods.

Salgado shares her room, one of four in an apartment near Jamaica Hospital Center, with her 13-year-old daughter and 7-year-old son, whose birthday they just celebrated a couple of weeks ago with cake and pasteles. One room is occupied by her sister (also an out-of-work household cleaner) and her son. A cousin who recently started getting some work in construction lives in the other room and Salgado’s niece and her son live in the final room.

She sent her daughter to quarantine with her aunt and cousin during the month of April. She wanted her to be around another girl near her age. Though they’d have daily video calls, keeping up with remote learning made the transition harder as her daughter had to wait a month before receiving the tablet needed to complete her schoolwork. She has to attend summer school this year.

“If you look at the numbers and the ethnicity and the demographics and the location of where the hardest-hit communities are, it has more to do with systematic racism, systematic defunding of programs, systematic marginalization of a certain community that leads to preexisting conditions, to health issues, to lack of work, to overcrowding situations and leads people to live two [or] three families in one house,” says Cruz.

Bludgeoned Job Sectors

Even before the pandemic began, business was not booming. On average, Salgado says she made $250 a week from cleaning gigs to cover her $600 monthly share of the rent, utilities, groceries and any other expenses.

Immigrants working in especially hard-hit job sectors that are also paired with increased exposure like food service, retail and personal care, and their struggle to access government relief programs created “a perfect storm of challenges for immigrant workers,” says Eli Dvorkin, policy director of A Center for An Urban Future, which co-published a report with the New York Immigration Coalition about COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on the city’s undocumented immigrants.

According to a survey of 244 predominantly Latinx adults and youth conducted in late April by Make the Road NY, a non-profit organization working for immigrant and working-class communities, 88 percent lost their jobs due to the pandemic. Additionally, a report from The New School’s Center of New York Affairs estimates that 192,000 undocumented workers have lost their jobs and that the city’s Latinx community has been hit hardest.

Salgado moved to New York City about 17 years ago from Honduras seeking greener pastures and to uplift her economic situation. She remains out of work.

Lack of Access to Public Assistance and Language Barriers

Though Salgado benefits from SNAP, she remains ineligible for Medicaid and has usually resorted to paying a one-time consultation fee of $15 at a local clinic. She has not been tested for COVID-19 yet, put off by the cramped clinic nearby.

Undocumented immigrants depend largely on themselves and the community-based organizations for financial support. While many had the security blanket of unemployment insurance — in some cases earning more than they were pre-pandemic – undocumented Latinx workers had little choice but to risk their health to earn a living. They also did not qualify for any of the federal stimulus packages. Lucero says that about 90 percent of MASA members fell into that category.

Language barriers also inhibited access to relief and made disseminating information incredibly challenging, says Dvorkin, pointing out the difficulty public entities and community-based organizations had keeping pace with the translation of shifting guidelines and changing information. And though Spanish is the second-most spoken language in the city, there is a large contingent of indigenous language speakers in the Latinx community who had an additional barrier.

“I think a lot of that happened when there was an interaction with a state or city agency that didn’t really have their shit together,” says Cruz, who added that she saw language barriers when her constituents sought to acquire tablets for their children’s remote learning or when trying to figure out how to bury a loved one. However, the basic information of wearing a mask and remaining six feet apart was successfully relayed.

Years of government distrust, accelerated by anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies coming out of President Trump’s administration, also limited outreach efforts to undocumented immigrants, says Dvorkin. But that public libraries stood out as a trusted vehicle of resources for undocumented immigrants, who have grown especially distrustful in the face of four years of federal anti-immigrant policies. “One of the most powerful tools that the city has to connect immigrants with public resources are libraries.”

According to a 2017 report by the New York City Department of Mental Health and Hygiene, 30 percent of foreign-born Latinos are uninsured. Central and South Americans are over three times as likely and Mexicans are six times as likely as non-Latinos to be uninsured.

Over half of the City’s Mexican population lacks access to health insurance.

Lucero says the uninsured figures for Mexicans are generous given that 85 to 90 percent of MASA’s adult members, 90 percent of whom are of Mexican descent, don’t have health insurance.

SOMOS Community Care, a non-profit, physician-led network of community health providers that serves nearly 800,000 immigrants has conducted more than 140,000 COVID-19 tests and opened some of the first testing sites in the city.

“We are the community doctors. We are the neighborhood doctors,” says Dr. Ramon Tallaj, the chairman of the organization’s board, explaining that a lot of the trust is derived from being embedded in the same area as patients and sharing similar backgrounds as those they treat. “The community knows that they have people out there like us, SOMOS doctors, immigrants like them who speak the same language. We are the same. We are them.”

The pandemic has taken an emotional toll on undocumented immigrants, but also those on the frontlines working to aid them.

“There were days where it was very exhausting because there are people who even if you know they needed help, there was nothing you could do for them because they had no status or because they were here by themselves and had no other family who could provide some support,” says Cruz.

“We have to step in to take care of our community. We understand that there’s a huge urgency right now, says Lucero.